Exodus 12:1-14, Psalm 149, Romans 13:8-14, Matthew 18:15-20

This is the second in my sermon series in which we test the terms of our draft new mission statement: Old First is a community of Jesus Christ in Brooklyn offering a space of unconditional welcome, a practice of worship and service, and a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven. This week: "a community offering a practice of worship and service."

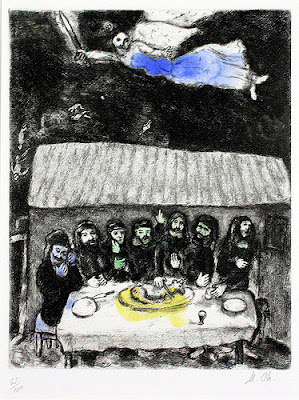

The very first practice of worship in the Bible is the Passover. The Passover was the first regular sacrifice that God instituted, the first communal meal to be repeated as a ritual. And every year Jews still celebrate the drama of their liberation, the Feast of Freedom, Pesach. We Christians celebrate a derivation of it every week. Passover is one of the two sources that the Lord Jesus blended to give us holy communion, also a supper of the lamb.

At sundown they slaughtered their lambs, as one, the very first costly thing that this collection of slaves ever freely did together. Then in common they stayed inside their homes to roast their lambs. In common they painted their doorposts and lintels with the blood of their lambs, and the blood was the means to distinguish them from the Egyptians around them, the only means.

The blood of the lamb is what spared them from the wrath of God upon the Egyptians and their gods and from the judgment of God upon their oppressors. They were spared, they were saved, not by their own revolt or war of liberation, but by believing in common the promise of the lamb. The meal is what made them a holy communion, and eating the meal is what nourished them for their first steps into freedom.

The Passover is wonderful and horrible. We are rightly horrified that God should have slaughtered all those Egyptian children, no matter how many Hebrew children the Egyptians themselves had killed. Two wrongs don’t make a right even for God. Of course, American history reminds us that no nation has ever let its slaves go free without bloodshed. And in ancient times, people just accepted that gods could act like this. But isn’t this God supposedly different, isn’t this God supposed to be moral?

We have to remember that Old Testament stories are not about morality. They’re not about justifying the good and condemning the bad. They’re rather about God’s election and God’s judgment — God’s election of a humble people, in this case Israel, and God’s judgment on a people of pride and prejudice, in this case Egypt.

So when we are troubled by questions about God’s jealousy and wrath, the Passover story does not address these questions; they are answered for us only in the distance, in the Passover of Jesus and his blood upon the post and lintel of the cross. Here in Exodus, election and judgment are displayed in naked conflict with the world. For us this conflict is only resolved in Christ, in whom God enters the world and takes the judgment and the wrath upon himself.

So the Passover story leaves you up in the air with morality unresolved, and you can come down to land only with the morality of Jesus. To read this wonderful and horrible story you have to be like an angel who passes over the violence, because on the doorposts of history you have haltingly spread the blood of Christ, the lamb of God. Agnus dei, qui tolles peccata mundi, miserere nobis. “O Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.”

But that first night, in fearful obedience to God, that night the tribes became a communion, the rabble became a congregation, the slaves became a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. This is the same transformation that we practice every week in worship too. We enter the room as individuals, open for something. We listen to God’s messages of judgment and love, we eat the sacred meal that celebrates our freedom, and we are transformed thereby into a communion of the lamb.

Maybe you did not ask to be transformed. You just wanted to add some God into your life. But the effect of this practice of worship is gradually to transform your whole view of the world—what you desire, what you value, what you long for. In a word, your culture. Instead of the world of the flesh on its own terms, even the best of the world on its own terms, you enter the culture of the Kingdom of Heaven, with different kinds of power, a different sort of freedom, and a different set of benefits.

The transformation was traumatic for Israel, as the later stories show. What God gave them they had not asked for nor planned for. They had not asked for freedom, just for some relief. They had not asked to leave their homes in Egypt, and they don’t know where they’re going. This God of Moses — they don’t know this God from Adam. After centuries of absence he suddenly remembers them, and says he’s on their side, and by signs and wonders he gives them what they had not asked for. And if this God did this to the Egyptians tonight, who knew what this God might do to them next week?

Even to escape the slaughter of the firstborn must have been traumatic. The wailing in Egypt outside their houses. They would have suffered the same fate as the Egyptians if not for believing the strange instructions. You see how it works: To survive the judgment you must believe in the judgment. If you trust the Word of this God, the judgment of this God frees you instead of punishing you. For them it was freedom from slavery in Egypt. In your case it’s freedom from the guilt and bondage of your sin. Without even waiting for you to confess your sins, God unexpectedly and gratuitously passes over them. You are free.

I did not say freedom from sin, not yet in this life. But freedom from the guilt and therefore from the bondage of your sin, and that’s the second practice after worship, the second practice of the Christian life, the practice of forgiving sins. Forgiving our own sins, which we can do appropriately by accepting God’s forgiveness and then learning to confess our sin. And forgiving the sins of others, the ones they do against us, and learning to do this appropriately and with justice and good mental health.

In our gospel lesson the Lord Jesus calls it the loosening of sin, from loosening the bonds of bondage. It’s a kind of freedom and also a kind of space, it’s your giving room to other sinners. It is a service that you offer. And it’s one part of offering a space of unconditional welcome. It’s a matter of practicing the roomy and spacious freedom of the culture of the kingdom of heaven, the culture of the dawn, the culture that you learn in worship, instead of the confining culture of the world, of darkness, of bondage, of punishment, of payback, of cause and effect.

Consider the method Our Lord lays out for us in Matthew 18, how you deal with an offense against you by someone also in the church. In the old culture you rightly take offense, and you complain to your allies and they owe loyalty against the offender. We do this all the time. It is being bound to the offense. In the new culture, you loosen the grip of the offense on you. You make space for yourself and for the offender. You go to the offender first, and you follow the steps to work it through.

Now in the end you might not achieve your hoped-for reconciliation, but already you’ve invested in the other person, and so you have implicitly begun the process of forgiveness already in yourself, and that means you are acting in your freedom. The method has its limitations when your offender is sick in the head or malicious or violent. And even at best the method is challenging, so you learn to just mostly not get offended. You keep raising the threshold of offense. You pass over their offenses against you. Or in the language of our epistle to the Romans, you owe no one anything. And then you’re really free.

If they don’t want to reconcile, you disconnect a bit, you give them space. You treat them as "a Gentile and a tax-collector." Now Jesus must have said this with a grin, because it was Gentiles and tax-collectors that he was always eating with and drinking with. When Jesus made a space, it was still always unconditional welcome. Now if I’m not as successfully forgiving as Jesus was, please don’t judge me, and I won’t judge you. But the point is clear: in the culture of the world, sin compels you and it compels your response to the sins of others. In the new culture, sin is there, sins exist, but they lose their power, they roar but they are in a cage. In the culture of freedom, sins are no longer occasions for compulsion but opportunities for the exercise of grace.

The space of unconditional welcome does not mean we will never offend each other, but rather that we are not bound by our offenses. We transform the culture of bondage to the culture of freedom, and we do this by our practices of worship and service. The freedom is owing no one anything, except to love one other. This is what you want. This is why you are here today. You came to worship to receive God’s love, the learn the culture of God’s love, and to share God’s love for all the world.

Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment