Brooklyn, New York—For his Atlantic Yards project Bruce Ratner promised a grandiose "urban room” and a tax generating office tower at the gridlocked Atlantic and Flatbush intersection at the heart of Brooklyn. He also promised to build "affordable housing.”

None of that is going to happen.

Instead, today the developer unveiled designs for an outdoor "public plaza” where the tower and atrium structure were promised, and told reporters at a press conference that his firm has no plans to build 15 of the 16 towers he promised to build, which would include nearly all of the "affordable” housing Ratner used to sell his plans to Mayor Bloomberg, Governor Paterson and a long list of other politicians.

"Ratner's not-so-pretty drawings of a barricaded, exhaust-enveloped plaza—including the absurd rendered fantasy of a traffic-less Atlantic and Flatbush intersection—is not the Atlantic Yards news of the day. The news of day, which is not surprising but is very troubling, is that Bruce Ratner admitted that he has no plans whatsoever to build the affordable housing he promised or the office tower he promised. It is crystal clear that Atlantic Yards is nothing but a scam, a money-losing arena, surrounded by massive parking lots, in the middle of a housing and unemployment crisis,” said Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn co-founder Daniel Goldstein.

"Bruce Ratner has broken every promise he has made to the public—Mayor Bloomberg, Governors Paterson, Pataki and Spitzer, Marty Markowitz, Senator Schumer, and all the politicians who rammed this debacle down Brooklyn's throat, owe the public a big explanation, and need to take this land back from Ratner since he is not going to meet any of his promises.”

There is one outstanding lawsuit challenging Atlantic Yards. The suit awaits a ruling from a Manhattan State Supreme Court judge. The case made by DDDB and its 21 community co-plaintiffs, is further bolstered by today's admission by Ratner that Atlantic Yards needs a new environmental review as it is not the project that received a rubberstamp environmental approval in 2006. The case was argued on June 30th.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Friday, September 24, 2010

Sermon for September 26, Proper 21: Prayer is Asking for Help

You can't always get what you want.

You can't always get what you want.

You can't always get what you want.

Buf if you try sometime, you find

You get what you need.

(The Glitter Twins)

Jeremiah 32:1-3a, 6-15, Psalm 91:1-6, 14-16, 1 Timothy 6:6-19, Luke 16:19-31

This is the only parable in which Jesus gives a character a name, so the name of the beggar is a key to the parable. What "Lazarus" means is "God helps."

At the beginning of the parable the rich man doesn’t think he needs God’s help, because his life is just fine. At the end of the parable he’s asking Lazarus to be sent back to help his brothers who are just like he was. Abraham answers that sending him back will not help them. They want to be blind. They want to be deaf to the words of Moses. They want to be self-indulgent and self-satisfied.

The parable has play in it—the rich man was being helped by Lazarus all along, just by lying at his door, just by his painful presence, he was offering the rich man a chance to be caring and kindly and generous. He was giving the rich man the chance to practice what Moses said about helping the needy and the poor. Lazarus was helping the rich man to be righteous and godly and faithful and loving and patient and gentle. But the rich man refused the help.

(You know we’ve been praying in this church for passionate spirituality. I wonder if God has answered our prayer by sending us Joe and Lacey. We cannot help them except by practicing passionate spirituality.)

What kind of help do you want from God? What kind of help do you pray for? It is right for you to ask for ordinary kinds of help. Jesus tells you this, in the Lord’s Prayer—you pray for your daily bread and you pray that God will save you from the time of trial. And when you pray Psalm 91, you pray for rescue and deliverance, you pray for safety in time of trouble. And in the Psalm God promises that, "When they call to me I will answer them."

People have been praying for help to the gods and goddesses since our evolution from the other primates. Help us when we hunt for meat. Help us when we plant our crops and harvest them. Help us in childbirth, help us in sickness, and help us when we die. The prayer for help is the most basic kind of prayer there is. You should do it. And the kind of help you pray for depends on the kinds of gods or goddesses you believe in.

The God we believe in is the God of Israel. The God we believe in is a covenantal God. A covenantal God is a God of faithful relationships, a God of promises, a God who talks to us, to everyone of us. The talk of God is recorded in the Bible, for the purpose that everyone of us can know what God says equally and publically. And what God has said is how God helps us. God helps us in many subtle ways, but the basic way God helps us is by what God has said.

That’s how God was helping the rich man, by what God said through Moses. God was helping the rich man to be a righteous man, but the rich man refused that help by ignoring what God had said.

God does not help us like the other gods and goddesses were thought to, by special favors here and there, by special preferences depending on how they like us. I know that many believers have this view of God today. "God help me with this, God give me that." Now I am not saying you should not pray like that. You should. "God help me get this a job. God help me with this task. God give us success, God bless our crops and industry, God heal me from this illness, God save me from death." Yes, pray that way. But you must pray this way by faith in God.

Whatever help you ask from God, you also need to say, "And let your will be done." Whatever particulars you ask of God, you also need to trust God’s providence. You need to trust that the providence of God for you may differ from the help you’re asking for. I know it personally. For many years I prayed for help in one thing and what God helped me with was something else, which now I’m very grateful for. But I still pray for help in terms of what I can see right now.

You see the dynamic with Jeremiah. Jeremiah was in jail and Jerusalem was under siege. The help that they were asking for was different than the help that God would give them. God would not free them now, because the siege was from God’s judgment. But God would give them back their future. They could count on it. You can invest in it, even if it’s right now under evil occupation. The help God gave to Jeremiah was help for his faith and for his hope.

This is the second sermon in my series on prayer. This week I’m saying that prayer is asking for help. Last week I said that prayer is managing the contradictions of our lives. These two aspects work together. Because as soon as you ask for help, you deal with the contradiction of your predicament against God’s promises. This disconnect, this gap, this chasm sometimes, this evident contradiction is what drives you to live by faith and hope and love. But God helps you with your faith and your hope by giving you all these wonderful words that feed your faith. You needs these words to keep believing, there are so many contradictions in the Christian life that if you don’t keep repeating the words of God your faith will fail.

But God helps you with another gift as well, the gift of the Holy Spirit, inside you, which you must believe is given to you without your having to feel it. This is the gift of God’s own power and personality inside you to help you understand God’s word that you can believe it, and the fire of God inside you to give you the hope you need to cross the disconnect, and the love of God inside you to give you the love you need to manage the contradictions in your life.

So what is the help that you should pray for? Let me repeat that you should keep on praying for the usual kinds of help. You should pray for help in time of need, in time of birth or illness or death, help to get that job, help to get that house, help to make ends meet, help for daily bread and help in time of trial and temptation. The typical particulars.

But you should also pray for the special help of the God of Israel, which is the help of God’s word and God’s spirit. Help me with your word, O God, and help me with your spirit, and then help me with these other things as well. You can keep on praying for the typical particulars if you also pray for the help of God’s word and God’s spirit.

But now let me exhort you to some atypical particulars, some unusual kinds of help to pray for. They’re in the epistle, chapter 6:11: "pursue righteousness, godliness, faith, love, endurance, gentleness." The way that I suggest you pursue them is to pray for them. Pray for help in getting that job, and also pray for help in righteousness. Pray for help in doing your job, and also pray for help in godliness. Pray for help in your finances, and also pray for help in living by your faith. Pray for help in dealing with your family, and also pray for help in love. Pray for help in healing your sickness, and also pray for help with endurance. Pray for help in having success in your life, pray for help in achieving your dreams and purposes, pray for help in making a difference in the world, and also pray for help with gentleness. Not just for yourself, but for our witness.

Our nation needs it desperately right now. Our nation is being ruined by the love of money, which is the opposite of godliness. All the evils that our nation is facing today have entangled roots, but at least one root of all of them is the love of money. And Christians who love money cannot be godly in their Christianity and cannot be gentle in their way of life. The religion that is needed by America is one of gentleness. Not a godliness of wars or violence or opposition or of burning books, but a godliness of gentleness. Not from weakness, but gentle from the strength of our endurance, gentle from the long endurance of our love, gentle from the toughness of our faith in God, gentle from our desire for righteousness.

God help us to be righteous and godly and gentle. God help us with your spirit and help us with your word. And having helped us with these first, then help us with everything else as well.

Copyright © 2010, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

The Ordeal of the Sermon

Click right here for a link to my short essay on preaching which was just published in Perspectives: A Journal of Reformed Thought.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Sermon for September 19, Proper 20: Prayer is How To Manage Contradictions

Jeremiah 8:18-9:1, Psalm 79:1-9, 1 Timothy 2:1-7, Luke 16:1-13

Some of Jesus’ parables are difficult. Like this one. Does Jesus really approve of a the dishonest manager? Is Jesus really advocating kickbacks? Doesn’t this contradict morality?

Remember that a parable is a story told on a curve. Jesus throws it like a curve ball. The pitch comes at you looking straight, and then at the plate it suddenly drops, and it moves inside and outside, where you don't expect it. A parable has play in it, it teases you, it resists you, it offends you, it judges you, and you have to let yourself be judged. To get it you have to give in to it. You can't stay standing in your normal stance. Your ideals of the good fall short of the actual reality of the world, the fallen world, the world which God loves but which is also under judgment.

A couple details. Verse 9: “Eternal homes” is literally, “pavilions of the age,” the pavilions of the kingdom that is coming. Think of great big party tents, pavilions of public feasting in the age to come, after the final judgment. To be part of that celebration then suggests you live right now in contradiction to including yourself among the best and the brightest. And you will be a lonely person in the kingdom of God if you try to stand on the goodness and the rightness of your morality and your mind. Give that up. Be accepted for the silly reality of what you are.

The word “wealth” is “mammon.” It doesn’t mean great wealth, but the common wealth of common people, your ordinary capital, your ordinary equity, your share in the economy of ordinary life. “Dishonest wealth” is a better translation than “unrighteous wealth.” Unclean wealth, unkosher wealth, crooked wealth. Like Jesus’ people having to use the Roman coinage with Caesar’s image on it, a constant violation of the second commandment. Just to participate in the economy was to keep breaking the commandment, making all their wealth unrighteous, no matter how honest their dealings or innocent their intentions.

Like our own participation in a world economy with its capitalist concentration of economic power, in a global system which increases the wealth of the wealthy and the poverty of the poor, exhausting our natural resources, and polluting the planet. We enjoy its benefits, but if we hold to the stance that our economic life is morally respectable or acceptable or even neutral, then this parable whizzes right by us, and we strike out. This parable has judged us. We are trying to serve two masters. We want to serve God, but we want to preserve our economic loyalties. So we all of us have to let ourselves be judged in order to face the reality of the contradictions of our life in this world every day. None of us can claim the stance of having solved it or of gotten it right. The wisdom here is for each of you to admit that whatever wealth you have is somewhat crooked.

The manager in the parable solved his problem by giving kickbacks. But the real point is that he did not try to defend himself or even plead his case. He just faced his own unrighteousness. You do the same, don’t stand on your innocence, just come to terms with your unrighteousness, be as shrewd in your own predicament as the manager was in his. Accept the judgment of God, don’t argue it or deny it. Accept yourself as contradictory. Don’t try to show the rightness of your mind or your morality. Don’t keep swinging. Just take the four balls. Get on base with a walk. Forget about your batting average. Live by grace, God=s grace, live by undeserved grace.

This sermon is the first in a series on prayer. Each week I’ll be asking the scripture lessons what they might tell us about prayer. This morning I’m saying that prayer is how we manage the contradictions of the world and the contradiction of our own selves. Look at the prayer which is Psalm 79. The Psalm comes to God with a problem. O God, we are supposed to be your chosen people, but look at our predicament. “The heathen have conquered the promised land, the temple is defiled, and Jerusalem is a ruin.” What happened to your promises, what happened to your faithfulness? “The harvest is past, the summer is ended, and we are not saved. How long, O Lord, will you be angry forever? Help us, deliver us, and forgive our sins, for your name’ sake.”

The prayers of Israel hold up the contradictions. The prayers of Israel are not idealistic, they do not smooth things over, they do not try to solve the contradictions or make things all add up. The prayers of Israel manage the contradictions just by holding them up to God. “Here is the situation, we cannot solve it or resolve it, we will not pretend we understand it, we will not pretend that we are in the right, we will only say that we need you desperately, and your forgiveness.”

The spirituality that is popular today prefers an idealistic unity. You know, everything comes together as one, and it all makes sense. But organized religion confronts us with contradictions. The liturgy in church gives words to the contradictions you live with every day, not least the contradiction of yourself. They way you manage your contradictions is by holding them up to God, by trusting in God=s mysterious responsibility, and kneeling down in your mind and body.

In St. Paul’s day, the greatest contradiction was to be the citizen of an empire that would kill you if it really understood what you believed. There was no separation of church and state, and Caesar claimed to be Savior, Lord, and Son of a God. When St. Paul made that very same claim for Jesus, he was being seditious. To be a Christian in the Roman Empire was to be in constant contradiction. The eventual persecution was inevitable, once the authorities figured it out. And yet St. Paul exhorted Timothy to keep praying for God to bless the authorities.

We do that too. We pray together, we hold up to God this world of contradictions and conflict, and we hold up to God the predicament of our own inescapable unrighteousness. Prayer is not a solution, it’s not a resolution, but it is an engagement, and an action, and an active reconciliation. And it’s the only way to live in love within the midst of all the frustration and the anger and the hatred.

I have told you this story once before, and it’s not a parable, so I’m telling it to you straight. I know a woman named “Deborah”, from Chile, in South America. She is a jeweler, but she was also a political activist, and she had worked in opposition to the dictator General Pinochet. She got arrested and interrogated by the CIA and tortured. They broke her fingers and her hands were soft like rags. One of the torturers demanded that she maker her a ring like the one they had taken from her. How could she do this? With her hands like this? For her torturer? She said she would do it if she could also make something special for herself. The torturer shouted, “Nothing political.” Deborah answered, “No, I want to make a Star of David. I am a Jew.”

It took her five days to make that piece of jewelry. As she made it she could feel her fingers heal and her hands made whole. She told me that the whole time she was making it, she could sense the Shekinah of God—the glorious presence of God—right there in the prison with her.

You can believe this story. It is true. Her making that jewelry was a kind of prayer. You can do the same thing when you pray, if not so extreme. If you want to pray, begin by choosing one of the psalms of contradiction, giving words to the contradiction of yourself and of the world. Pray that same psalm over every day. The solution will not come to you in the logic of philosophy or science or even theology. And it will not come to you in your feelings but in your faith. Your solution is the humble silence of the knowledge of God, the knowledge of the mystery of God and the grace of God.

Yes, you can start your praying with the Psalms of Israel. And I can offer you real hope, from my own experience and the experience of many other people, that if you keep on praying the Psalms, you will make yourself be present to God and God will be present to you. The hope you have is not a feeling but a being. God’s own person is your hope.

Copyright © 2010, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.

Please note: the piece of jewelry at the top of this posting is the actual piece of jewelry that Deborah made in prison.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

Sermon for September 12, Proper 19, Nine Years After Nine Eleven

Photos courtesy of Jane Barber

Jeremiah 4:11-12, Psalm 14, 1 Timothy 1:12-17, Luke 16:1-13

Jesus poses these two parables as questions. “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep,” and then, “What woman, having ten silver coins.” To the second one the answer is obvious: “Any woman would.” But to the first one the answer is the opposite: “No one would.” No one would stupidly risk the ninety-nine for the sake of the one. You would simply write off that last sheep as normal business management. What’s a one percent loss, when standard depreciation is ten percent?

The answers are opposite, but Jesus combines these two parables. He means that your answer to the second question makes you go back again to the first question and answer it contradictorily.

Not “No one would,” but “Anyone of us should risk the ninety-nine to save the one.” Jesus is saying, “Maybe you wouldn’t do it, but I would.” The Messiah would. The Messiah would because God does. To God, every lost person is of inestimable worth, the most despicable, the least acceptable, the most unfit. To bring such a one is what God rejoices in.

It’s what the cops and firemen and rescue workers did, nine years ago, while the buildings were still burning, and then in the first days after the attack. They counted every last lost person to be of inestimable value, no matter who it was. Even at the cost of their own lives. Which one of you would do the same?

You know that my coming here as your pastor was bound up with 9/11. Nine years ago, on the Sunday after the attack, I preached my candidating sermon, and on these same scripture lessons. They were remarkably relevant, especially the Jeremiah text, which gave words to the disaster. First, God speaking:“A hot wind comes from me out of the desert, toward my poor people, not to winnow or to cleanse, a wind too strong for that. Now it is I who speak in judgment against them.” Then the prophet reporting, “I looked on the earth, and it was waste and void, and to the heavens, but they had no light. I looked, and the birds had fled, I looked, and the cities were laid in ruins before the Lord, before his fierce anger.”

Nine years ago some fundamentalist preachers interpreted the terrorist attack as the judgment of God on America, for this sin or for that. They were wrong. I can tell you that God does not use such violent means to judge us. Our Reformed tradition teaches that all such violent kinds of judgment came to a definite and discernible ending at the death of Christ. God’s judgments are simply and cleanly offered in the words of the scriptures, God’s judgments are freely and earnestly offered for your reading and your understanding. God does not communicate with us by sending us sickness or loss or terror, God does not use violence of any kind to judge us. God judges us graciously in the words of Jesus and the apostles, God judges us faithfully in words of the law and the prophets. We read and mark and learn these words, we inwardly digest them, and by God’s grace we judge ourselves.

9/11 was not a judgment sent from God, but it was certainly an incentive and opportunity for our self-examination. Not to excuse the terrorists, but for us to fall to our own knees for mercy. To return to the Gospel, to judge ourselves by the Law of God again, because it’s always our privilege to be judged by God. Yes, it is our privilege to judge ourselves by the Word of God.

Those preachers were wrong to say that God had sent those terrorists as a judgment on America, but I prefer that mistake to so many of the later co-options of 9/11, as we are seeing now again. To stir up anger against the rest of the world and to respond to the violence with our own violence and our own Christian holy war. As if America had the right to righteous anger, as if we are a special sacred Christian nation about to be profaned by the knees of Muslim men at prayer. As if it were God’s job only to bless America and not to judge us. As if our society does not stand in constant need of mercy. And losing our conviction of needing mercy, our nation is losing our capacity for joy.

The gospel reveals the truer legacy of 9/11, that of the shepherd risking everything for that one sheep, the firemen in the stairwells giving their lives to save the lost, and then digging in the rubble for one more survivor or their last remains, the legacy that every single person, no matter what race or religion, is a silver coin of absolute value. We Christians stand for a society which spares no effort in the rescue of every victim—the victims of terrorists, but also the forgotten victims of our ordinary way of life, the unnoticed victims of the underside of our economy and those who live in the shadows of our great society. We Christians stand for an America that is rich in reconciliation and most powerful in mercy.

Our scripture lessons speak of judgment and of joy. These two words are joined by the hinge of mercy. Mercy is rich. Mercy is grace and generosity. Mercy is self-giving and self-sacrifice. We stand in mercy, we can stand up straight in mercy when we have bowed down low in receiving mercy from a righteous God who judges us in love and reconciliation. We accept the privilege of being judged by God, we come to know ourselves in terms of mercy, and what that yields in us is joy. From judgment through mercy to joy. We Christians and Jews and Muslims are alive to the mysteries of mercy, and we stand for a society which God blesses by judging, not by violence but in God’s word, which calls us out to joy. Not this anger that we see today, not this hatred, this bitterness, this self-righteousness, this fear. But judgment and mercy and joy.

I don’t remember what I said in that sermon I preached nine years ago. I don’t remember having noticed that I preached it on the twenty-first anniversary of my ordination. As Abraham Lincoln said, “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” I don’t expect you to long remember what I tell you on my thirtieth anniversary. But I offer you my testimony, which echoes the testimony of the Apostle Paul in our second lesson.

I can tell you without reserve that I have never been so joyful in my life. Oh yes, I have my burdens and frustrations, I have my own share of grief that I live with, but these are only the sandbars in the daily river of my joy. When I came back from Canada I found myself joyful to get back to work. It gives me so much joy to be the pastor of this church, that I should be here now, with you.

It gives me so much joy to have you people in my life, with all your personalities and your talents and your interests and your desires and your trouble. It gives me joy to face the challenges we share. It gives me joy to have the privilege of leading you, of preaching to you and teaching you, of interpreting the Bible for you—that I get to study the Bible on your behalf, that I get to pray for you and be prayed for by you. Who am I? That I should serve a church that has welcomed an imam to pray here? That I should serve a church that hosts a synagogue for High Holy Days? That I can worship with Jews right here in our own sanctuary is a high point in my ministry. That I should serve a Reformed church that celebrates holy communion every week, that I serve a church that welcomes everyone no matter what their sexuality, that I serve church that welcomes me, that I should serve a congregation 356 years old—O brave old church, that has such people in it.

But most of all it gives me such great joy that I have been the recipient of so much mercy. Mercy from my children, mercy from my family and my friends, mercy from the consistory, mercy from the classis, mercy from those who love me and mercy from those who don’t. I accept all of your judgments of me as true. And I thank you for your mercy. Especially the mercy of my wife, my companion and my lover and the chief joy my life. But most of all, the mercy of God. New every morning, I stand in mercy every day, and that’s what generates my joy.

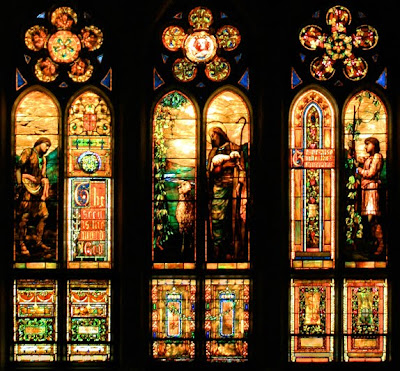

Look at that stained glass window there, the triptych in the north wall. Notice all the colors in it, the joyful colors in it, the signs of the bread and the wine, the banquet of our joy. And look Jesus and the sheep. That’s where I see myself today. The Lord Jesus there, he daily comes to find me in his mercy. He counts me worthy to stand next to him, and he carries me when I need carrying. He is the savior who saves me and brings me safe to God, and I am joyful to serve him as my Lord.

Copyright © 2010, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.

Sunday, September 05, 2010

Sermon for September 5, Proper 18, "The Unbearable Lightness of Being"

(Painting by Sir Stanley Spencer) Jeremiah 18:1-11, Psalm 139:1-6, 13-18, Philemon 1-21, Luke 14:25-33

(Painting by Sir Stanley Spencer) Jeremiah 18:1-11, Psalm 139:1-6, 13-18, Philemon 1-21, Luke 14:25-33Why was Jesus so extreme, that you have to give up all your possessions? Does it even work? Wouldn’t you just be dependent on someone else who has possessions? Like a Buddhist monk? ike St. Francis of Assisi and Mother Teresa? Or let’s say you have small children—there’s a lot of plastic toys you could give up, but all your possessions would be irresponsible. Now I don’t like to resort to not taking Jesus literally. His words are clear. But how do we obey him and still have a realistic life?

Jesus is on his campaign toward Jerusalem. The crowds keep increasing. They think that Jesus is leading a regime change, and they want to be on his side when it happens. They’re excited, his kingdom is at hand. So Jesus gives them fair warning. "I want you under no illusions. What I will deliver is not what you’re expecting. It may cost you everything. Whatever you value, let go of it now, or do not follow me."

That was the message for them. What’s the message for us? Does God mean to scare us off? You want to get close to God, that’s why you’re here, you are drawn to Jesus, you want him to make a difference in your life, but when you get close to him, he turns around and talks like this, to renounce all your substance and your relationships and all that you hold precious.

We should not soften this hard saying of Jesus. "To follow me you must give up all your possessions." Let’s keep it as something hard and challenging, something to reckon with. If you have a place on your refrigerator for nice sayings, add a place for hard sayings, and put this one there. Jesus presents us with a problem we cannot solve, or make to go away. He gives you a problem to live with all your life. You have to keep coming back to this and measuring yourself against it, examine yourself, judge yourself. Always question the reasons by which you convince yourself that you need this thing, or that connection, or this arrangement.

God places no value on your affluence. God has no interest in protecting your possessions for you, or of getting you more of them. That’s not what God does for you. God’s opinion about your possessions is right here in Luke 14. We have to keep coming back to that. We keep returning to the sober realization that the Christian life is as often a life of loss as it is of gain. It will cost you. Especially when you’re aiming for justice and righteousness in a world that is bent towards injustice and ungodliness, then you will often feel like you are losing, not winning. In this world, to accomplish any real kind of moral change requires that you must sacrifice, maybe even your life.

That’s the meaning of carrying your cross. When Jesus said these words to the crowd, the cross was not yet the religious symbol of Christianity. When Jesus said these words to the crowd the cross was a symbol of Roman domination. Rome had occupied their country, they were a subject people, they had no civil rights, even in their own land they were not citizens. The punishment of crucifixion was one of the things that kept them in line. It was a slow and painful death in the full view of the public, to keep the people down. When they saw you carrying your cross, you were a dead man walking. Unfairly or not, you were a goner.

"Jesus, is that what you’re saying, that we should live as losers to the power of the world, surrendering to injustice? Can’t we be winners, can’t we be heroes? Are you saying not to arm ourselves against oppression, not to stand with courage and fight it, risking death with pride? You mean to surrender to it, like losers with our crosses on our shoulders?"

No. It’s precisely because Jesus did not surrender that they killed him. It’s because he kept saying exactly what he wanted and did exactly as he willed. In that sense they had no power over him. He was free to the end, but he knew it would cost him. How much do you want to be free?

If you are carrying your cross, you cannot carry a sword. When will the world ever learn this? That the only way to accomplish any justice and progress in the world is not by carrying weapons but by carrying the cross. Every movement, and every nation, must return to this.

Notice that Jesus says, "Your own cross." Not the Roman cross. Three times he says it, "one’s own cross." The Romans may seem to be the problem, and while it is true that they are unfair, the real problem is always yourself. It also means that it’s not your possessions themselves that are your problem, but you who possesses them. It’s your possessing that you have to renounce and let go of—the world you build around yourself, how you define yourself, what you’re invested in. Your problem is not what you have but your having. Your enemy is you.

I once had a parishioner whose husband treated her badly. She put up with it, and always said, "He is my cross to bear." No he’s not. That’s not right. She was bearing her husband’s cross instead of her own. As long as she was bearing his, he didn’t have to, and she was kept from bearing her own. The possession she had to give up was her marriage to that man. But had she done that, all her family would have reviled her. Her husband’s family, yes, but her own family too. They would have accused her of disloyalty and selfishness.

That’s what Jesus means when he says you have to hate your father and mother, he doesn’t mean the internal emotion, he means the external reputation, that your family accuses you of not considering them, or of not loving them enough. They act all offended at you, and sometimes that’s the cost of discipleship. They may cut you off from their good graces and their sympathy; and that’s when you realize that you have begun to carry your cross. "If you follow me to Jerusalem, these are the issues and trials and temptations you will face. Are you ready for it?"

Discipleship is a stretch. Christians have to stretch towards obedience and devotion. Yet your discipleship is the most important thing in your life, even worth dying for. Not as a hero—heroes don’t get crucified, they win. No, in the far less glamorous service of ordinary life, of family life, the way you deal with your parents or your spouse or your kids or your own siblings, that’s where discipleship is costly. And in ordinary economic life, the things you buy and sell, the things you own, what you take care of. Everything counts. We’re always counting the cost of discipleship.

The crowd got bigger anyway, even as he entered Jerusalem. But when the pressure got too high they deserted him. He cost too much. Finally even the twelve disciples deserted him. They didn’t want to get near any crosses. So on the basis of what he says here, did that mean that they could no longer be his disciples? Does this mean that none of us can be his disciples?

You know, ironically, Jesus didn’t carry his own cross even though he died on it. An African named Simon of Cyrene carried it for him. There’s a mystical exchange in the gospel. Jesus did the dying so that you don’t have to. Jesus does the dying but not the carrying, You do the carrying but not the dying. His death has virtue for you, to free you from the domination of death. If you carry your cross, you will die not on it, but in peace. You are not carrying it towards the crucifixion but away from it.

There is a mystery of exchange and substitution here, of ransom and replacement. Your cross is for yourself, your reminder of the challenges of Jesus in terms of the life ahead, very down-to-earth. You measure yourself only by his words, and that gives you freedom. You discover that the cross is light. It looks terribly heavy until you shoulder it, and then it’s light. When you have given up everything, in the way that Jesus says, you discover that the unbearable lightness of your being is not unbearable but joyful. You carry your cross away from the crucifixion, you carry it lightly, as a testimony of your gratitude and thanksgiving.

Copyright © 2010, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)