Friday, September 29, 2017

October 1, Proper 21, Space, Practice, Vision #5: God "In Service"

Exodus 17:1-7, Psalm 78:1-4, 12-16, Philippians 2:1-13, Matthew 21:23-32

This is the fifth sermon in my series called Space, Practice, Vision. I am testing the terms of our draft new mission statement against the scripture lessons every week. This is the statement: Old First Reformed Church is a community of Jesus Christ in Brooklyn, offering a space of unconditional welcome, a practice of worship and service, and a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven.

The last phrase is my favorite, “a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven.” But some of you have told me that you’d rather that phrase be something else. I mentioned this to my wife Melody last week, and she said, “Me too.” What! She offered some different language which she thinks says it better. And maybe so! You’ll have to ask her yourself.

I like the phrase because it’s both Biblical and evocative. I hear the “kingdom of heaven” as expansive, inclusive, embracing, and uplifting. But what if others hear it as the opposite, as judgmental and restricting and confining? Especially with the rise of the Christian Right?

That’s a real consideration, and it’s up to the consistory eventually to decide. Please understand that this sermon is not meant to make a case for whatever final version of the new mission statement, only that the image of the kingdom of heaven is so much in the Bible that we need to know what it means.

Let me take a step back. Last Sunday the Germans had their election and one of the right-wing politicians from the AfD made this statement: “In Germany, Muslims are allowed, but not Islam.” Why? Because Islam does not distinguish the sacred from the secular, and at its root it is a political religion, and look, in Saudi Arabia Christians are allowed but not Christianity. Many Germans want their nation to be Christian by law. And you know of Americans who want the same. This is not just fundamentalism. To dismiss this merely as fundamentalism is to misunderstand religion.

The American strategy of pluralism has been to make religion a private matter, which liberals take for granted. Your religion is for your soul and your personal behavior, but not for public policy. We erect a wall of separation between the church and state, and it’s the state that gets to decide where the wall is. We’ve squeezed our religions into boxes to keep them safe, but also to keep us safe from our religions.

Because religions actually do make claims on public policies, religions have theocratic claims, public claims, political claims. Islam, for example, was never meant to be just a private religion for Muslims, but a vision for the whole of society, including the government.

And now in America the Christian Right is rejecting our strategy for pluralism. If Jesus is King of Kings, and since the word “king” is obviously political, then America must be a Christian nation again. (And also capitalist and nationalist, just not Christian socialist!) So if that’s what people hear in the phrase, “a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven,” then I can understand the hesitation.

No matter what we say in our mission statement, it is for this congregation to testify to a whole different vision of the kingdom of heaven, and in our spaces and our practices for us to model it. The culture of this kingdom is determined by the character of the king from whom it extends. So the vision begins is focused on Jesus, and where he takes his throne.

His only throne on earth is a cross. While in heaven he is seated on the right hand of his Father, on earth he is enthroned upon a cross. Crux probat omnia, the cross (judges) changes everything, or at least it should.

Crucifixion was not a Jewish thing. The Jews did not crucify people. The chief priests were not allowed to crucify Jesus, they had to ask Pontius Pilate to do it. Crucifixion was a Roman thing. It was how they punished their slaves. When the Romans crucified Jesus, and posted above his head that he was the king of the Jews, they were showing that a Jewish king was no more than a slave to them: “This cross is the kind of throne we Romans give to Jewish kings.”

So when St. Paul says in his famous passage in Philippians 2 that Jesus “emptied himself and took the form of a slave,” his reference is precisely to the slave on the cross: Jesus, displayed to the Roman world as the king who is a slave, and St. Paul daringly says that Jesus freely took it on as his self-expression.

We don’t know how St. Paul died, there is no record. But he would not have been crucified, because he was born a Roman citizen. He had privilege. Jesus did not. In American terms, Paul was white and Jesus was black. At least slavery among the Romans was not defined by the racism that we built America upon. And there were Roman slaves of high-status owners who were given lots of power and discretion. A Roman slave could do many things an American slave could not do.

But it was still slavery, because the point of slavery is not what you cannot do but what you may not do. No matter how much power you have, you may not use your power in your own interest, but in the interest of your owner. Freedom means the freedom to pursue your own interests. But slaves must sacrifice their own interests, even their children, to the interests of their owners. And just so St. Paul writes that you are empowered to “look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others.” Why? Because the king of this kingdom is enthroned on earth as a slave upon a Roman cross.

St. Paul writes, “have this same mind in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be grasped at, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave.” I’m sorry this translation is inaccurate. The word “though” is not in the Greek; it’s more correctly, “who being in the form of God.” In other words it’s just like God to act this way. Maybe not like Jupiter or Zeus, but just like the God of the Exodus who took the form of a servant for his people.

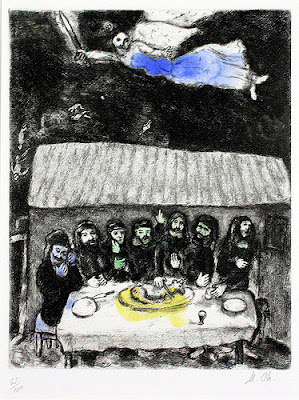

Do you see it? The people were thirsty and there was no water and they complained. Moses was offended, but God was not. God said to Moses, “Take your staff, the one with which you struck the Nile, and strike the rock where I will be standing before you.” Why didn’t God just send a powerful bolt of lightning down to break the rock open? Why did God stand there at the rock like Mr. Carson from Downton Abbey, as Lady Mary cuts her meat, as Moses breaks the rock. Like Daisy the kitchen maid, God put Godself “in service;” there in the desert God put God’s own servanthood on display.

So the slavery of Jesus is the extreme expression of the service of the God of Israel. That mind that was in Christ Jesus is the mind of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The culture of the kingdom of Jesus on earth is the culture of the kingdom of heaven. A sovereignty of service. A dominion of surrender to the interests of others. And in America today it is so important that this vision of the kingdom of heaven, this truer vision, is the vision that our congregation witnesses to by our space of unconditional welcome and that we model by our practices of worship and service.

According to St. Paul, our concern is not a Christian America, but to be Christians in America. If he says that we should in humility regard others as better than ourselves, then shouldn’t we regard non-Christians as better than ourselves? Should we not look to the interest of Muslims as the interest of the church? How can we say otherwise?

I’m not downplaying the Lordship of Christ. I’m not saying that all religions are finally the same. I’m not talking about what Jesus cannot do but what we may not do. I am not countering the vision of St. Paul that “at the name of Jesus every knee shall bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, the glory of God the Father.” I’m talking about how in the meantime the Lord Jesus expects us to bear witness to his Lordship.

I close with this. I was at a conference of ministers where one of my colleagues stated in good faith that the model of Christian discipleship is servanthood. Then one of our black pastors stood up and said, “We in the black church have had enough of that. You can say that for yourselves from your place of privilege. But please don’t come to a black church and tell us all to be servants.”

Got it! I get that servanthood is a metaphor, just as kingdom is a metaphor, and as a metaphor servanthood it is not always appropriate. We are called to freedom, not slavery, and God is able to take the form of servanthood because God is absolutely free. I would not force the metaphor of servanthood on a people whose salvation needs to be experienced as freedom and dignity.

The point of the metaphor is love, self-giving love. Your freedom is for your loving others in their own interests. The culture of the kingdom expresses the character of the king from whom it extends. And what pours out of him is the love of God. Have this same love in you that is in Christ.

Copyright © 2017, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.

Friday, September 22, 2017

September 24, Proper 20, Space, Practice, Vision # 4: Welcome to the Wilderness

Exodus 16:2-15, Psalm 105:1-6, 37-45, Philippians 1:21-30, Matthew 20:1-16

Monday morning, I sat up in bed and I said to Melody, “Another week of trying to get people to do stuff. And they already have too much to do.” Am I complaining? I love my job, it’s my privilege to be your pastor, but privately I’m a constant complainer. If I act nice in public, under my breath I’m always grousing and griping. It is a trial for my wife. I went with her to Costco last week and as we came back out to the parking lot she said, “I’m never taking you here again.”

So in the parable, that would be me complaining about the landowner’s generosity as a case of unfairness. In Exodus, that would be me filing a complaint about our hunger in the wilderness. I take offense at suffering. That would be me who is challenged by St. Paul in Philippians, that our suffering is a privilege, at least when it’s for Christ. And I suspect that challenges you as well.

In the parable, the joke is that what the vineyard workers complain about is grace. Not the principle of grace but the effect of grace. The principle of grace is that you get gifts from God you have not earned and do not merit. The effect of grace is that other people can get gifts from God that you don’t get. “Hey, yes you gave me enough, but they suffered less for it! This grace thing feels unfair.”

One of the difficult lessons of the Christian life is that God is not accountable to our human notions of fairness. That the world is unfair we learn to cope with from an early age. But when God feels unfair, well that’s like growing up with unfair parents: your brother got a better bike than you did, your troubles did not receive the same attention as your sister’s. It takes real faith to keep believing in God when the lives of other believers seem more blessed than your own.

This living by faith is in itself a kind of suffering, suffering as endurance, as enduring while not receiving. Having faith in a God who does not answer to your experience of fairness is a kind of suffering, the suffering you do for Christ, which St. Paul calls your privilege! St. Paul can be such a Calvinist!

Everybody knows that the ethical life is choosing for the right against the wrong, for what is fair against what isn’t fair. But what about when choosing for the right will cost you unfairly, or cost you things that other people get to keep? That too is a kind of suffering, and that too requires to live by faith, that the right thing is its own reward, that the cost is itself the benefit. You have to live by faith that love wins, because with love the cost is the same thing as the benefit.

It sounds glib when it comes from me. What do I know of real suffering? That I’ve been treated unfairly by the denomination that I love? First world problem. So don’t take it from me, take it from St. Paul, who knew of what he spoke. He wrote these words from prison. He had to spend his most productive years in prison, like Muhammad Ali, like Nelson Mandela, and his imprisonment was totally unfair. False incarceration. He was confined in conditions of isolation, and yet, from his soul he extended out across the empire a great space of unconditional welcome. His privilege.

Last week I spoke about the space of unconditional welcome in very glowing terms. This week the plot thickens, because that space does not exclude your suffering. The space of unconditional welcome can be a wilderness. A place of testing and temptation. A bare and empty space, that gives you no accouterments, no conveniences, no comforts and no furniture. No groceries. All cost and no benefits. And maybe no vision, no vision of the kingdom of heaven to encourage you, just the empty space with no conditions of comfort.

Into the wilderness God welcomes the Children of Israel, this god they do not know from Adam. The gods and goddesses of Egypt they understand, but not this new god who has forced them here. Is his palace on that legendary mountain where they have to go to meet him?

Whoever he is, they’re now his guests, in his realm, and as his guests they feel he is obliged to feed them. Or maybe they felt like they are the slaves of this god who bought them from the Egyptians at the price of blood, and so as his slaves they have the right to rations. In either case, it’s up to God to feed them. Their complaint seems to be legitimate. God does not contend the point.

What upsets Moses is the way they ask for it, the tone of their complaint, insulting God, and slandering the liberation God has won for them. Talking about their former enslavement as the good old days. Ingrates! Well, they’re hungry. And afraid. And traumatized by the violence of their liberation. They had not asked for freedom, only for relief. They have no experience at freedom, and freedom is scary. They don’t know what to expect from this god, and their slavery has trained them in distrust and resistance. They are passive-aggressive, untrusting, always acting victimized.

God designs their daily rations to be a testing, a proving, a training in obedience. Not the old obedience of slavery but the new obedience of freedom. The obedience of trust instead of the whip, by faith instead of force. You go out every morning to collect your food, but you get only enough for each day. If you keep it a second day it spoils, except what you collect on the sixth day, which will be twice as much and will not spoil for the Sabbath Day. “Give us this day our daily bread.”

Notice it’s not, Give me this day my daily bread, because no matter how much or little you collect, everybody has just enough. So too in the parable of the vineyard, every worker got the same pay no matter how long and hard they worked. They grumbled that the landowner made them equal! Socialism! What happens to initiative! Making everybody equal isn’t fair. Give me this day my daily bread! But the bread God gives us is to share. In the parable, it’s to share and share alike, but in Exodus it’s to share according to our need. In the wilderness God trains in communion.

This training in obedience is a training in receptivity, the receptivity to grace, because it’s grace that will get you through the wilderness. You need training in receiving grace. You resist receiving it even when you need it, so God trains you in receptivity, and for that God welcomes you into the wilderness. Are you in a wilderness in your life? How much baggage are you still depending on?

What was the wilderness in Philippi, what was the suffering of the Philippians? The effect of their baptisms was to make them undocumented aliens in their own land. Dreamers whose DACA status has been revoked. Worse yet, allegiance to the Lord Jesus was treason against the Lord Caesar. This was the threat they lived with every day. A constant low-grade suffering that might break out in violence and beatings at any time. Unfair indeed, because for Jesus’ sake they kept honoring Caesar far more than he deserved. Their freedom in Christ was worth it, the benefit was more than equal to the cost, but living by faith is its own kind of suffering, enduring, holding on and holding up.

The space of unconditional welcome can be a wilderness, and it’s God who welcomes you into it. And when you find yourself complaining, it’s precisely in your complaining that you must seek for God. You must look deeper into your wilderness to see God’s glory.

I’m not talking about the power of positive thinking. I’m not talking about turning mountains into goldmines and lemons into lemonade. I’m saying that what you are complaining about is what God is testing you in, your wilderness is your proving ground. “The flame shall not hurt you, I only design / your dross to consume and your gold to refine.” Your gold is your collection plate, your bowl for gathering manna, not your success but your receptivity to God’s grace within your life, God’s presence in your life. I can attest that this has been true for me, and I myself did not welcome it, it was painful and I was afraid and I complained to God, but it was true and good and hopeful, because what I was given was God’s self.

One last thought. When the space of unconditional welcome is a wilderness, we’re still called to be a community of Jesus, especially then. And that means that when you are in your suffering, it is the privilege of the rest of us in this community to suffer your complaining and make space in our lives for you, to welcome your emptiness into our lives. As unconditionally as we know how. We give you the gift of ourselves to go along with the gift of God’s own self, and sometimes the gift of ourselves may have to stand in for God when God feels absent or unfair.

You don’t have to earn this gift of ourselves from us, it is grace, and you don’t have to worry that it might cost us, because the cost is the same as the benefit, because it is love and that’s the way it is with love, when it’s the love of God that needs no benefit and spares no cost.

Copyright © 2017, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.

Thursday, September 14, 2017

September 17, Proper 19: Space, Practice, Vision #3: A Space of Unconditional Welcome

Exodus 14:19-31, Psalm 114, Romans 14:1-12, Matthew 18:21-35

This is the third installment in my sermon series Space, Practice, Vision, in which we test the terms of our draft new mission statement: Old First is a community of Jesus Christ in Brooklyn offering a space of unconditional welcome, a practice of worship and service, and a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven.

This week: a community offering a space of unconditional welcome.

The first chapter of the Book of Genesis sings the song of God making space, space within the chaos of the ancient deep. Great space, safe space, for the tender flourishing of life. Space under the lofty ceiling of the firmament. Space between the waters for dry land to appear. Space for birds above and creeping things below. God began this work by God’s Spirit moving over the face of the primeval deep, the wind of God upon the waters.

God did something similar in the Exodus. The exodus of the Israelites through the Red Sea recapitulates Genesis. When Moses stretched out his hand, the wind of God blew over the waters and divided the sea to make dry land, between the walls of water on their right hand and their left. It was a long, thin space towards their escape. It was a great long hallway into freedom.

But the welcome in this space was not unconditional. The welcome for the Israelites was a trap for the Egyptians and the death of them. This is taken by Exodus as just and right, that life for one group means death for another, that some are in and some are out, and the walls of God’s design are there to protect us from our evil enemies.

Unconditional welcome is not natural. Animals don’t practice it, no nation practices it, even when it’s our ideal. Human communities don’t practice it. Our welcoming each other naturally is conditional. We welcome you if you do not threaten us and our young, if you do not threaten our comfort or our treasure, nor our allies with whom we have allegiances. In the realm of religion, we welcome you if you fit our holiness code (not that we ourselves ever measure up to it). Right now a group in the Reformed Church is working to keep our churches unwelcoming to Christians who are gay or lesbian.

What else is new. It’s the way of the world, but it’s not the kingdom of heaven. The death and resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ is the end of all exclusion, all separation, all distinction. His royal welcome is so lavish and total and unconditional that the church hardly believes it and rarely practices it. But the space of unconditional welcome is the earthly image of the vision of the kingdom of heaven.

Now let me tell you a story. Sixteen years ago yesterday, at the Flatbush church, I preached my candidating sermon to become your pastor. The search committee was there to hear me, including Lindsay, Peter, Jane, and Cecilia. It was the Sunday right after 9/11. I mention in passing that the lectionary texts that Sunday were miraculously relevant to the devastation of the World Trade Center.

That Friday we had driven here from Grand Rapids, Michigan, and we drove because all the flights were grounded. Rick Stazesky was driving, Melody up front, and me in the back seat working on my sermon. From the Tappan Zee Bridge we got our first sight of the smoke. Soon we saw fighter jets patrolling overhead and then military vehicles on the Triboro Bridge, and I broke down sobbing in the back. From the BQE you couldn’t take your eyes off the hideous column of smoke.

Rick drove us into Park Slope, and we saw our first good thing. The front doors of this church were open. People were sitting on the stoop and in the doorways and the narthex, with lighted candles all around. People were sitting in the sanctuary, some of them in groups. On the walls long sheets of newsprint were hanging and people had written their prayers on them. The prayers were from all different religions and some things written were against religion. No problem—the welcome was unconditional.

We learned that the sanctuary had been open all week. We learned that very soon after the airplanes hit, while the debris from the burning was raining down on Brooklyn, someone from this congregation had opened up the doors and started making quiet music. In the shadow of the terror, people came in, seeking refuge, seeking sanctuary, and here was sanctuary. Someone hung up the prayer sheets.

I’m not sure who it was, but it wasn’t the pastor, you didn’t have one then. The interim pastor was stuck out in New Jersey. Someone of the congregation had the vision of a space of unconditional welcome. And on that Friday, when Melody and I saw what we saw, we knew we wanted to come here.

Do you know that what you did that week changed the church’s reputation in the community? Before that we were regarded as the mighty fortress, deservedly or not. Did you know that only the center of the narthex was open, and the outer doors at either end, below the steeple and the porte-cochere, were sealed shut and never opened because both ends of the narthex were closed off for storage? That hallway there was also full of storage and cabinets that blocked the doors to the alley. A mighty fortress.

Since then we’ve gradually opened things up to make the space more welcoming. Decluttering, cleaning, opening windows, rebuilding windows, opening doors, removing pews, making room, making space. It is true and paradoxical that in such a great big building it takes constant work to offer space.

Just as in your community of Jesus it takes constant work to keep offering emotional, social, and spiritual space, constant re-imagining the vision. It is true and not paradoxical that in order to make this community a space of welcome you have to keep doing your own personal inner decluttering. Making room and space within yourself. Which brings us to our gospel lesson from Matthew 18.

The parable of the king and the two slaves has a comic ending. Melody says to think of the king as Tony Soprano and the first slave as one of his capos who owes him money. Tony lets him. Then Tony finds out the capo he let off easy won’t let off an underling for far less dough, and Tony takes that as disrespect. So he has the capo tortured, to teach him some respect.

The point is that you forgive the sins of other people against you if only out of respect for God. If you don’t forgive other people, you are disrespecting God. The comic point of Jesus here is that you forgive the sins of others finally not because you yourself are such a saint, but because you fear God! Or at least show some respect for God and what God has done for you! Who do you think you are, not to forgive? Hasn’t God forgiven you seventy-seven times?

Think of the practice of forgiving sins as your internal decluttering. You make yourself free of that thing they did you, and that insult is no obstacle, and this unfairness is no longer in the way. You just don’t want that on you any more, what they did to you.

Now if what they did to you was hurtful injury, and the damage remains and the pain keeps coming back, you’re going to have to forgive them for the same sin every day for years. If they can’t change, you make space between you and even disconnect from them altogether in order to be able to forgive them. Otherwise you’ll be so busy having to forgive their every new sin that you won’t have space in your life to welcome other people who really need you.

The practice of welcoming is taught by the Epistle to the Romans. St. Paul tells the community of Jesus to offer room within it for people who practice their religion with opposing practices. If you abstain, you abstain to the Lord. If you eat, you eat to the Lord. Here too it’s a matter of respect to the Lord.

And if the other person’s religious practice is hurtful or racist or homophobic, then you invoke last week’s section of Matthew 18, when Jesus called us to try reconciliation first, and if that doesn’t work, to bring it to the church. You take it to Tony Soprano. Which is why we have the Board of Elders, our collective mob boss, for spiritual muscle and respect. It’s hard, it’s hard to do both, to have a community which is a real community and also to offer unconditional welcome. It isn’t natural, which may be why more churches don’t do it, but the vision is worth keeping ever before us, because it’s the vision of the kingdom of heaven.

Here’s how we’re going to keep it before us: with a symbol and a story. The great big symbol is our sanctuary, a living symbol, an active symbol that actually is what it symbolizes. You are restoring it for mission, to give back to the public community its great, safe space of unconditional welcome. It is for you and for your worship, but no less is it for people who are not you, but who are God’s.

And the story is what you did here sixteen years ago, before I came. You need to tell that story every year to be reminded of the mission that God has given you. You need to tell that story as a love story, the tale of how someone saw how to express the love of God for all the people of the world.

Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Friday, September 08, 2017

September 10, Proper 18: Space, Practice, Vision #2: A Practice of Worship and Service

Exodus 12:1-14, Psalm 149, Romans 13:8-14, Matthew 18:15-20

This is the second in my sermon series in which we test the terms of our draft new mission statement: Old First is a community of Jesus Christ in Brooklyn offering a space of unconditional welcome, a practice of worship and service, and a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven. This week: "a community offering a practice of worship and service."

The very first practice of worship in the Bible is the Passover. The Passover was the first regular sacrifice that God instituted, the first communal meal to be repeated as a ritual. And every year Jews still celebrate the drama of their liberation, the Feast of Freedom, Pesach. We Christians celebrate a derivation of it every week. Passover is one of the two sources that the Lord Jesus blended to give us holy communion, also a supper of the lamb.

At sundown they slaughtered their lambs, as one, the very first costly thing that this collection of slaves ever freely did together. Then in common they stayed inside their homes to roast their lambs. In common they painted their doorposts and lintels with the blood of their lambs, and the blood was the means to distinguish them from the Egyptians around them, the only means.

The blood of the lamb is what spared them from the wrath of God upon the Egyptians and their gods and from the judgment of God upon their oppressors. They were spared, they were saved, not by their own revolt or war of liberation, but by believing in common the promise of the lamb. The meal is what made them a holy communion, and eating the meal is what nourished them for their first steps into freedom.

The Passover is wonderful and horrible. We are rightly horrified that God should have slaughtered all those Egyptian children, no matter how many Hebrew children the Egyptians themselves had killed. Two wrongs don’t make a right even for God. Of course, American history reminds us that no nation has ever let its slaves go free without bloodshed. And in ancient times, people just accepted that gods could act like this. But isn’t this God supposedly different, isn’t this God supposed to be moral?

We have to remember that Old Testament stories are not about morality. They’re not about justifying the good and condemning the bad. They’re rather about God’s election and God’s judgment — God’s election of a humble people, in this case Israel, and God’s judgment on a people of pride and prejudice, in this case Egypt.

So when we are troubled by questions about God’s jealousy and wrath, the Passover story does not address these questions; they are answered for us only in the distance, in the Passover of Jesus and his blood upon the post and lintel of the cross. Here in Exodus, election and judgment are displayed in naked conflict with the world. For us this conflict is only resolved in Christ, in whom God enters the world and takes the judgment and the wrath upon himself.

So the Passover story leaves you up in the air with morality unresolved, and you can come down to land only with the morality of Jesus. To read this wonderful and horrible story you have to be like an angel who passes over the violence, because on the doorposts of history you have haltingly spread the blood of Christ, the lamb of God. Agnus dei, qui tolles peccata mundi, miserere nobis. “O Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.”

But that first night, in fearful obedience to God, that night the tribes became a communion, the rabble became a congregation, the slaves became a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. This is the same transformation that we practice every week in worship too. We enter the room as individuals, open for something. We listen to God’s messages of judgment and love, we eat the sacred meal that celebrates our freedom, and we are transformed thereby into a communion of the lamb.

Maybe you did not ask to be transformed. You just wanted to add some God into your life. But the effect of this practice of worship is gradually to transform your whole view of the world—what you desire, what you value, what you long for. In a word, your culture. Instead of the world of the flesh on its own terms, even the best of the world on its own terms, you enter the culture of the Kingdom of Heaven, with different kinds of power, a different sort of freedom, and a different set of benefits.

The transformation was traumatic for Israel, as the later stories show. What God gave them they had not asked for nor planned for. They had not asked for freedom, just for some relief. They had not asked to leave their homes in Egypt, and they don’t know where they’re going. This God of Moses — they don’t know this God from Adam. After centuries of absence he suddenly remembers them, and says he’s on their side, and by signs and wonders he gives them what they had not asked for. And if this God did this to the Egyptians tonight, who knew what this God might do to them next week?

Even to escape the slaughter of the firstborn must have been traumatic. The wailing in Egypt outside their houses. They would have suffered the same fate as the Egyptians if not for believing the strange instructions. You see how it works: To survive the judgment you must believe in the judgment. If you trust the Word of this God, the judgment of this God frees you instead of punishing you. For them it was freedom from slavery in Egypt. In your case it’s freedom from the guilt and bondage of your sin. Without even waiting for you to confess your sins, God unexpectedly and gratuitously passes over them. You are free.

I did not say freedom from sin, not yet in this life. But freedom from the guilt and therefore from the bondage of your sin, and that’s the second practice after worship, the second practice of the Christian life, the practice of forgiving sins. Forgiving our own sins, which we can do appropriately by accepting God’s forgiveness and then learning to confess our sin. And forgiving the sins of others, the ones they do against us, and learning to do this appropriately and with justice and good mental health.

In our gospel lesson the Lord Jesus calls it the loosening of sin, from loosening the bonds of bondage. It’s a kind of freedom and also a kind of space, it’s your giving room to other sinners. It is a service that you offer. And it’s one part of offering a space of unconditional welcome. It’s a matter of practicing the roomy and spacious freedom of the culture of the kingdom of heaven, the culture of the dawn, the culture that you learn in worship, instead of the confining culture of the world, of darkness, of bondage, of punishment, of payback, of cause and effect.

Consider the method Our Lord lays out for us in Matthew 18, how you deal with an offense against you by someone also in the church. In the old culture you rightly take offense, and you complain to your allies and they owe loyalty against the offender. We do this all the time. It is being bound to the offense. In the new culture, you loosen the grip of the offense on you. You make space for yourself and for the offender. You go to the offender first, and you follow the steps to work it through.

Now in the end you might not achieve your hoped-for reconciliation, but already you’ve invested in the other person, and so you have implicitly begun the process of forgiveness already in yourself, and that means you are acting in your freedom. The method has its limitations when your offender is sick in the head or malicious or violent. And even at best the method is challenging, so you learn to just mostly not get offended. You keep raising the threshold of offense. You pass over their offenses against you. Or in the language of our epistle to the Romans, you owe no one anything. And then you’re really free.

If they don’t want to reconcile, you disconnect a bit, you give them space. You treat them as "a Gentile and a tax-collector." Now Jesus must have said this with a grin, because it was Gentiles and tax-collectors that he was always eating with and drinking with. When Jesus made a space, it was still always unconditional welcome. Now if I’m not as successfully forgiving as Jesus was, please don’t judge me, and I won’t judge you. But the point is clear: in the culture of the world, sin compels you and it compels your response to the sins of others. In the new culture, sin is there, sins exist, but they lose their power, they roar but they are in a cage. In the culture of freedom, sins are no longer occasions for compulsion but opportunities for the exercise of grace.

The space of unconditional welcome does not mean we will never offend each other, but rather that we are not bound by our offenses. We transform the culture of bondage to the culture of freedom, and we do this by our practices of worship and service. The freedom is owing no one anything, except to love one other. This is what you want. This is why you are here today. You came to worship to receive God’s love, the learn the culture of God’s love, and to share God’s love for all the world.

Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

This is the second in my sermon series in which we test the terms of our draft new mission statement: Old First is a community of Jesus Christ in Brooklyn offering a space of unconditional welcome, a practice of worship and service, and a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven. This week: "a community offering a practice of worship and service."

The very first practice of worship in the Bible is the Passover. The Passover was the first regular sacrifice that God instituted, the first communal meal to be repeated as a ritual. And every year Jews still celebrate the drama of their liberation, the Feast of Freedom, Pesach. We Christians celebrate a derivation of it every week. Passover is one of the two sources that the Lord Jesus blended to give us holy communion, also a supper of the lamb.

At sundown they slaughtered their lambs, as one, the very first costly thing that this collection of slaves ever freely did together. Then in common they stayed inside their homes to roast their lambs. In common they painted their doorposts and lintels with the blood of their lambs, and the blood was the means to distinguish them from the Egyptians around them, the only means.

The blood of the lamb is what spared them from the wrath of God upon the Egyptians and their gods and from the judgment of God upon their oppressors. They were spared, they were saved, not by their own revolt or war of liberation, but by believing in common the promise of the lamb. The meal is what made them a holy communion, and eating the meal is what nourished them for their first steps into freedom.

The Passover is wonderful and horrible. We are rightly horrified that God should have slaughtered all those Egyptian children, no matter how many Hebrew children the Egyptians themselves had killed. Two wrongs don’t make a right even for God. Of course, American history reminds us that no nation has ever let its slaves go free without bloodshed. And in ancient times, people just accepted that gods could act like this. But isn’t this God supposedly different, isn’t this God supposed to be moral?

We have to remember that Old Testament stories are not about morality. They’re not about justifying the good and condemning the bad. They’re rather about God’s election and God’s judgment — God’s election of a humble people, in this case Israel, and God’s judgment on a people of pride and prejudice, in this case Egypt.

So when we are troubled by questions about God’s jealousy and wrath, the Passover story does not address these questions; they are answered for us only in the distance, in the Passover of Jesus and his blood upon the post and lintel of the cross. Here in Exodus, election and judgment are displayed in naked conflict with the world. For us this conflict is only resolved in Christ, in whom God enters the world and takes the judgment and the wrath upon himself.

So the Passover story leaves you up in the air with morality unresolved, and you can come down to land only with the morality of Jesus. To read this wonderful and horrible story you have to be like an angel who passes over the violence, because on the doorposts of history you have haltingly spread the blood of Christ, the lamb of God. Agnus dei, qui tolles peccata mundi, miserere nobis. “O Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.”

But that first night, in fearful obedience to God, that night the tribes became a communion, the rabble became a congregation, the slaves became a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. This is the same transformation that we practice every week in worship too. We enter the room as individuals, open for something. We listen to God’s messages of judgment and love, we eat the sacred meal that celebrates our freedom, and we are transformed thereby into a communion of the lamb.

Maybe you did not ask to be transformed. You just wanted to add some God into your life. But the effect of this practice of worship is gradually to transform your whole view of the world—what you desire, what you value, what you long for. In a word, your culture. Instead of the world of the flesh on its own terms, even the best of the world on its own terms, you enter the culture of the Kingdom of Heaven, with different kinds of power, a different sort of freedom, and a different set of benefits.

The transformation was traumatic for Israel, as the later stories show. What God gave them they had not asked for nor planned for. They had not asked for freedom, just for some relief. They had not asked to leave their homes in Egypt, and they don’t know where they’re going. This God of Moses — they don’t know this God from Adam. After centuries of absence he suddenly remembers them, and says he’s on their side, and by signs and wonders he gives them what they had not asked for. And if this God did this to the Egyptians tonight, who knew what this God might do to them next week?

Even to escape the slaughter of the firstborn must have been traumatic. The wailing in Egypt outside their houses. They would have suffered the same fate as the Egyptians if not for believing the strange instructions. You see how it works: To survive the judgment you must believe in the judgment. If you trust the Word of this God, the judgment of this God frees you instead of punishing you. For them it was freedom from slavery in Egypt. In your case it’s freedom from the guilt and bondage of your sin. Without even waiting for you to confess your sins, God unexpectedly and gratuitously passes over them. You are free.

I did not say freedom from sin, not yet in this life. But freedom from the guilt and therefore from the bondage of your sin, and that’s the second practice after worship, the second practice of the Christian life, the practice of forgiving sins. Forgiving our own sins, which we can do appropriately by accepting God’s forgiveness and then learning to confess our sin. And forgiving the sins of others, the ones they do against us, and learning to do this appropriately and with justice and good mental health.

In our gospel lesson the Lord Jesus calls it the loosening of sin, from loosening the bonds of bondage. It’s a kind of freedom and also a kind of space, it’s your giving room to other sinners. It is a service that you offer. And it’s one part of offering a space of unconditional welcome. It’s a matter of practicing the roomy and spacious freedom of the culture of the kingdom of heaven, the culture of the dawn, the culture that you learn in worship, instead of the confining culture of the world, of darkness, of bondage, of punishment, of payback, of cause and effect.

Consider the method Our Lord lays out for us in Matthew 18, how you deal with an offense against you by someone also in the church. In the old culture you rightly take offense, and you complain to your allies and they owe loyalty against the offender. We do this all the time. It is being bound to the offense. In the new culture, you loosen the grip of the offense on you. You make space for yourself and for the offender. You go to the offender first, and you follow the steps to work it through.

Now in the end you might not achieve your hoped-for reconciliation, but already you’ve invested in the other person, and so you have implicitly begun the process of forgiveness already in yourself, and that means you are acting in your freedom. The method has its limitations when your offender is sick in the head or malicious or violent. And even at best the method is challenging, so you learn to just mostly not get offended. You keep raising the threshold of offense. You pass over their offenses against you. Or in the language of our epistle to the Romans, you owe no one anything. And then you’re really free.

If they don’t want to reconcile, you disconnect a bit, you give them space. You treat them as "a Gentile and a tax-collector." Now Jesus must have said this with a grin, because it was Gentiles and tax-collectors that he was always eating with and drinking with. When Jesus made a space, it was still always unconditional welcome. Now if I’m not as successfully forgiving as Jesus was, please don’t judge me, and I won’t judge you. But the point is clear: in the culture of the world, sin compels you and it compels your response to the sins of others. In the new culture, sin is there, sins exist, but they lose their power, they roar but they are in a cage. In the culture of freedom, sins are no longer occasions for compulsion but opportunities for the exercise of grace.

The space of unconditional welcome does not mean we will never offend each other, but rather that we are not bound by our offenses. We transform the culture of bondage to the culture of freedom, and we do this by our practices of worship and service. The freedom is owing no one anything, except to love one other. This is what you want. This is why you are here today. You came to worship to receive God’s love, the learn the culture of God’s love, and to share God’s love for all the world.

Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Saturday, September 02, 2017

September 3, Proper 17; Space / Practice / Vision #1: A Vision of the Kingdom of Heaven

Exodus 3:1-15, Psalm 105, Romans 12:9-21, Matthew 16:21-28

I’m starting a new sermon series today. It’s called A Space, A Practice, A Vision, and for the next ten Sundays I’ll be asking the scripture lessons every week to speak to one or more of those three themes: a Space, a Practice, a Vision.

Why those three words? I have taken them from the draft new mission statement for our church that our consistory has been working on. You see, when I came here sixteen years ago, one of my first jobs was to develop a mission statement, which we did, and that mission statement has been guiding us since, and you hear me quote from it every Sunday as the welcome in our service. It has served us well, but over the years I’ve come to feel it as too inward—welcoming people in, but not directing us back out, nor speaking of God’s mission to the world outside our doors.

So now the consistory is working on a new mission statement. This time it’s being drafted by them and not by me. When the drafting team gave its first report to the consistory last Spring, I was so moved by their proposal I got emotional. It’s not final yet, and it’s part of a larger process of casting a vision for Old First. So why not contribute to the process with a sermon series, to let the Bible speak to the statement, to give some better certainty that is what God wants for us.

So here it is: Old First Reformed Church is a community of Jesus Christ in Brooklyn, offering a space of unconditional welcome, a practice of worship and service, and a vision of the Kingdom of Heaven.

You will notice that the first part of the statement is the same as our current one. Our church is a community, a community defined by our source and center in Jesus Christ and not by any other commonality of identity. Our community exists not just for ourselves and our benefit, but to offer something, something for God, and something for the world around us.

What do we offer? Three things. First, a space of unconditional welcome. Space that is literal and figurative—physical space, sanctuary space, big space, beautiful space, sacred space, shelter space, meeting space, concert space, rehearsal space, public space, and also social space, spiritual space, healing space, emotional space, inclusive space, room, room for you, room for individuality and diversity. Absolute hospitality, unconditional welcome.

But not empty space, for in this space we offer, second, a practice of worship and service. We practice certain practices designed to worship God in a way that leads to welcome and inclusion and healing and service to each other and also service to the world. Our practices make movement in the space, in and up and down and out again. This part of the mission carries us out beyond our inwardness.

Please notice that our first lesson from Exodus speaks to Space, and our second lesson from Romans speaks to Practice.

In Exodus, from the burning bush, God makes a promise to Moses: “I know the sufferings of my people, and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians, and to bring them up out of that land to a good and broad land (that’s the Space), a land flowing with milk and honey (it’s not an empty Space, it’s a healthy Space, a healing Space), to the country of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites.”

So no, it’s not empty space, there are other people living in it. It’s not a welcoming space or inclusive space, and for the Israelites to take that Space they’ll have to remove the other people from it by violence with a Holy War. Which is what Peter was expecting the Messiah do with the Romans.

There are Christians today who are saying on the media and in support of this current President that because that holy violence is in the Bible it is Biblical for us to do. But St. Paul says quite clearly otherwise in Romans 12, in his list of Christian practices of worship and service.

When he says “leave room for the wrath of God, make space for the wrath of God,” he means the space of judgment and wrath is off limits for us who follow Christ. In that space, we are not allowed. “If your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them drink. Never avenge yourselves. So far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all.” Of course that is difficult, of course that’s challenging and maybe costly and dangerous. It may feel like giving in, surrender, even collaboration, if you enemies are the ones in power.

The only way to sustain it is by practicing the practices of worship and service laid out clearly in the chapter. We are told to “Rejoice in hope,” so we practice rejoicing and hoping counter-culturally. We are told to “Be patient in suffering, and persevere in prayer,” which is not passive indifference but active intervention but knowing our limits and lifting the trouble up to God. We are told to “contribute to the needs of the saints,” so we support this community of Jesus with our money, and we are told to “extend hospitality to strangers,” so we labor to keep a capacious building open that does just that.

It is rewarding and fulfilling. But you have to get over the hump and through the resistance of it feeling like sacrifice, because it means the sacrifice of your entitlements according to the world. The Lord Jesus does want you to gain your life, but his counter-cultural challenge is that in some real sense you have to lose your life in order to find it. The sacrifice of your natural entitlement is what he means by taking up your cross. And to take up your cross, you also have to let go of your sword and self-defense.

That’s what Peter did not see yet. Peter wanted to say, “Blood and soil, our blood, our soil,” and he wanted the Messiah to fight for that. He figured it was Biblical, like the Christian-nationalists today. But to this temptation we have to say, Get thee behind us, Satan. Not because we are more righteous. But because we have met the enemy and it is us. We are the enemy whom Jesus feeds, with his own broken body. We are the enemy whom Jesus gives to drink, with his own blood.

Peter did not yet see the vision of the Kingdom of Heaven that Jesus could see. Yes, Peter would see it before he tasted death, but only after the death and resurrection of his Lord. St. Paul came to see it too, and life inside it is what he describes in Romans 12 with his list of practices. The practices of worship and service are meant to be evidence of the over-arching vision, the dream, the hope, and the third part of our draft new mission statement, my favorite part, a vision of the kingdom of heaven.

The kingdom of heaven is not for escape to heaven but for the full salvation of this world. And maybe other worlds and planets too, who knows. We believe that the salvation of this world requires us to pay attention to this world, but if we see the world from only within in the world, our sight is distorted, depressed, and distracted.

If we see the world only from within the world, then we’re going to be like Peter and reject the way of the cross, of death and resurrection. If we see the world from only within the world we’re going to want to carry guns instead of our crosses. We think we are being realistic, but the world in itself does not know itself. In order to see the world rightly we have to see it from the perspective of heaven. To serve the world with both love and justice we have to view it with the x-ray vision of the kingdom of heaven.

I invite you to look for the kingdom of heaven, because only then can you make sense of losing your life to find it. And I invite you to believe the promise of Jesus, that when you lose your life for his sake you will find it, because when you accept his promise you will start to see the kingdom of heaven. I know it’s circular and also counter-cultural, but I invite you into it.

One last word. He told us to pray for it. He told us to pray: Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, in earth, as it is in heaven. Because it hasn’t fully come we pray for it. On earth God’s will is certainly not being done. But it is being done in heaven. It’s not just that God gives space to our resistance and rebellion, but God is so subtly powerful to weave our disobedience into God’s grander strategy and great design.

Yes, not just powerful, but weaving, embracing, incorporating, absorbing—in other words, loving. We want this church to offer a vision of the kingdom of heaven because we want this church to offer the overwhelming height and depth and breadth and length of the love of God.

Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)