Saturday, November 26, 2016

November 27, Advent 1: Violence #1: War

Isaiah 2:1-5, Psalm 122, Romans 13:11-14, Matthew 24:36-44

This is the first in a sermon series on violence. We’re asking the scripture lessons every week to tell us about violence. Now this is not a jolly theme for the happy holidays. But Advent is a penitential season, and repentance means facing hard realities, and the hard reality is that America is a violent country, the most violent of the great democracies.

It’s true that violence is natural. “Nature is red in tooth and claw.” Adolf Hitler once said, “I cannot see why man should not be just as cruel as nature.” But nature seems to be getting more violent of late, at least the weather is, thanks to our messing things up. And civic violence has found new expression and encouragement by the President-elect, despite the real distress and real concerns of so many people who did vote for him. The worst of it was the Access-Hollywood tape when he boasted of assaulting women and rejoiced in talk of raping them.

To “make America great again” should we threaten war to enforce our interests around the world? To “make America great again” should we resume our assault upon the landscape, the biosphere, the atmosphere, the water, the carbon in the ground, not to mention the poor of the earth whom we need to exploit for the cheapness of the products we consume? Forty years ago President Jimmy Carter called us to repentance on such things and we hated it. “We have nothing to repent of! We are great, and now we shall be great again in those things in which a violent nation can be great.” That’s what we’re looking at. And Advent is a season of repentance.

Repentance requires realism. We shan’t be idealistic. The gospel is anything but idealistic. The Bible is realistic about violence. People are put off by the violence in the Bible, but its violence is realistic. The Judges were violent, Joshua was violent, the Children of Israel were violent, David was violent, prophets called for violence, and God did not just tolerate violence, God committed it.

On the other hand, the Creation account in the Bible is distinctly non-violent when compared to the ancient mythologies. In the mythologies, violence was regarded as essential to existence, and the world was formed as a product of the wars between the gods. But the God of the Bible spoke the world into being, absolutely peacefully. God said, Let there be light, and that light made space in the universal darkness. God said, Let there be a firmament, to hold back the natural chaos and disorder and make a great safe space for the freedom of birds and fish, and then God spoke to push the water back to make dry land, for plants and animals and humankind to flourish in. And it was good.

But humankind rebelled and brought the violence back in. Cain killed Abel, and then down to the days of Noah violence increased upon the earth, and normalized, as normal as eating and drinking, as marrying and giving in marriage, warfare increased until God released the waters back and washed it away. Yes, with natural violence God dealt with human violence. But then, with the rainbow, God said, I won’t do that again. God is in process with violence, step by step repudiating it.

You can make the Bible justify violence, as you can make the Bible justify anything. The Bible is not a systematic book of good ideas, well-thought out and organized. It’s a collection of stories, the story of God within the stories of real people in the real world, of fallen people in a fallen world. We have to read these individual stories in terms of the single, over-arching story, and the story of the love of God in Jesus Christ trumps every other story. The anti-violence of the Lord Jesus is the story that puts the other violent stories in their place.

We read the stories of the violence of the Judges as the stories that long for the Messiah of God, and the stories of the wars of Israel are put to rest in the Prince of Peace. The prophecies that the Messiah would lead a holy war and smash the heads of his enemies were laid to rest with the Jesus in the tomb. We read the stories of violence in the Bible to remind us to repent of our own works of darkness in general and of our own knack for violence in particular, our toleration of it, our excusing it, our taking of our ease and wealth from it. In Advent we repent.

We will not be idealistic. Violence is natural and even of necessity. All nations are violent. Civilization is not the absence of violence but the organization of it. The civil authority has a monopoly on violence to make for safety and order. Except in America, where we refuse the government its monopoly on violence because the private handgun is a sacred fetish of our civil religion. We claim a civil right to kill another person at our own discretion, so it’s only natural that our police departments defend themselves with military weaponry. We descend to the state of nature with its necessity of war, even low-level war domestically. Like in the days of Noah, and the sea-level is rising.

It’s because violence is natural that the prophecy of the Lord Jesus in today’s Gospel is always true and will always be relevant until he comes again. Within the darkness keep awake! Be yourself a space of light within the darkness, make a space in the chaos of nature for freedom and safety and peace. To keep awake in the dark is to exercise your freedom from the necessity of nature. The gift of salvation is freedom, freedom from the power of sin, freedom from payback, freedom from the law of club and fang, freedom from the fear of death, freedom from the iron claims of violence.

Freedom from some things means freedom within other things, the other things we don’t escape until the Lord Jesus comes again. You are not free from the world but free within the world. You are not free from nature but free within nature. You are not free from necessity but free within necessity. You are not free from violence but free within violence. You are not free from war but you are free within war.

What does this mean? I don’t know fully yet, and what I have to say today is tentative, but I ask you to be open to where this conversation may lead us in the coming weeks. Here’s my report for today:

There will be war, and we can’t escape it, we can’t pretend it won’t be necessary. We will not be idealistic, and humanistic efforts at appeasement may well make things worse. But the realism of Christians says that wars do not solve problems, they only postpone them and recast them. There is no good war, no just war, even when it’s necessary, and every war makes another war. Making war is not what makes a nation great. If we have to submit to violence to defend our families or the Jews among us or the Muslims or whomever, then at the same time we must grieve it, and mourn it, and not pretend we’ve made the world a safer place by having done it. And we may never, never equate our national interests with the advancement of the Kingdom of God.

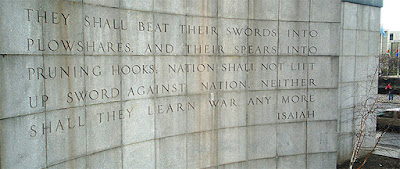

In Manhattan, at the United Nations, you can see a monumental inscription of the wonderful words from Isaiah about “beating our swords into plowshares and learning war no more.” But actually in Isaiah it’s not the nations who are able to make peace among themselves, it’s rather God who makes peace among the nations by God judging them, by God deciding between them, God arbitrates between them with a binding arbitration.

The sober reality of the Christian gospel is that the peace among the nations is not an achievement of the nations themselves, for nations are naturally violent, but wherever peace occurs it’s only ever from the judgment of God upon the nations. Peace is never a matter of human progress but of God’s judgment pushing back against us, pushing back against our works of darkness. And the way that we receive God’s judgment by way of repentance.

Repentance is a liberation. When you recognize the darkness, you can look for light. The good news here is that the nations of the world, for all our darkness, really do long for the light. So says Isaiah. This good news is the mission that God has given us in all of this. For out of Zion shall go forth instruction and the word of the Lord. We are entrusted with the word of the Lord, and many peoples shall come and say, “Come let us go up to the house of the Lord, come let us walk in the light of the Lord!”

Copyright © 2016 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Thursday, November 17, 2016

November 20, Ingathering Sunday; Prayer and Action #8: The Today of the Lord

Jeremiah 23:1-6, Benedictus, Colossians 1:11-20, Luke 23:33-43

“Today,” says Jesus. What did Jesus mean by “today” when he said it to the criminal? “Today you will go with me to heaven?” But the Lord Jesus did not go to heaven that day. He descended to the dead that day, and he stayed dead for two more days. So what Jesus was promising this criminal must have been something other than his going to heaven when he died.

Let me translate what Jesus said more literally: “Amen, I’m telling you, today you’ll be with me in the paradise.” What is “the paradise,” why that specific word, the only time in all the gospels?

The word back then was not a synonym for “heaven.” It had specific worldly meaning. A paradise was a royal park, a palace garden, like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, like the Garden of Eden, a private park for an emperor’s enjoyment, where he might take his special guests to walk and talk with him, and where to be invited was a privilege of honor. Like the White House Rose Garden.

If we respect the metaphor, this means that Jesus was giving this criminal more than he’d asked for. He’d only dared ask to be remembered in the Kingdom, but Jesus brings him into the royal garden. He’d only asked for some carnations on his grave, but Jesus puts a rose in his tuxedo.

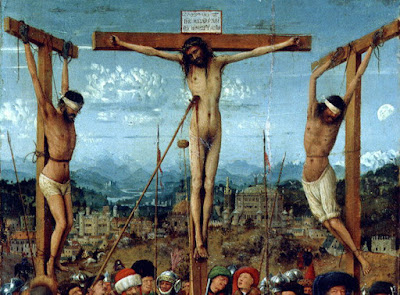

What a strange exchange between these two upon their crosses. What things to be saying when you are dying in defeat. Has their pain made them delirious? “Jesus, remember me, when you come into your kingdom.” What possible kingdom? It was precisely to prevent his Kingdom that Jesus was being killed. There’s an inscription above the head of Jesus which reads, “The King of the Judeans is this guy,” but that is meant for mockery. It means, “This is what we Romans do to Jewish kings!”

But this criminal somehow believes that Jesus could die his death and still get his kingdom in the end, that God will bring him back alive for some miraculous liberation. “So Jesus, when that day comes, grant me a pardon; I was with you; don’t forget me; don’t let my name be blotted out.”

The answer is unexpected: “Amen, today.” That is a royal proclamation. Jesus is already acting the king, right now. He does what kings do in granting him a royal pardon, and he invites him to his royal garden. Jesus has made a Garden of Eden upon this ugly hill they called The Skull, Golgotha.

The criminal assumed that Jesus’ kingdom would come after the crucifixion, but Jesus believed that his kingdom was established by the crucifixion; that when the soldiers put him on the cross, they put him on his throne; that in killing him, his enemies were giving him his kingdom; and that Pontius Pilate, in mocking him with that inscription, was doing his official duty of proclaiming him.

The prophecy of Jeremiah has come true. The Son of David has begun to reign, but upon the cross, and the pardoning and welcoming of this criminal is the first act of the new administration. This criminal is made the opposite of Adam and Eve. From his sin he’s welcomed back into the Garden. A lost sheep of Israel has been gathered by this shepherd, as Jeremiah prophesied. And in the words of Colossians, the criminal has been “rescued from the power of darkness and transferred into the kingdom of the beloved Son, in whom he has redemption, the forgiveness of his sins.”

A crack is broken in the surface of the earth. A great crack is broken in the hard shell of human history. From the foot of the cross the crack runs back through time, breaking open all the misery and loss of Israel, back through the woeful dynasty of David, all the way back to Genesis, all the way back through the gate of the Garden of Eden, the crack runs to the dead tree in the middle, and the dead tree comes to life again, and the green spreads out across the ground.

From the same foot of the cross the crack runs forward too, into the future, under us and off beyond our sight, breaking open the hard shell of humanity, fracturing our monuments of mastery, crumbling our achievements into rubble and dust, and the soft green shoots rise up there as well. In the words of Leonard Cohen, “There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.”

I’m trying to imagine this strange wonder of how the cross of Jesus Christ has power across the span of human history, that the death of Jesus has some virtue beyond that single day. I’m trying to imagine how the Kingdom of God is with us and also yet beyond us, I’m offering an image of how the Kingdom of God is both powerless and powerful. This dying man, a paradigm of the powerless, is also the pinnacle of power and an emperor of peace.

I propose to you that for us to see the Kingdom of God we have always to see it with two eyes, two contrasting visions, both envisioned by the Lord Jesus, both true, but neither true just on its own. (The following adapted from Jacques Ellul’s Violence, pp. 44-45.)

First, the Kingdom of God is out there, majestic, cosmic, impending, over-arching, all-inclusive, the life of the world to come, the future always pressing down on us, judging everything, keeping us always discontent. In the light of this Kingdom we must examine everything and question everything. The cross judges everything. We may never be content with any human system. Every advance in church and society must be analyzed and criticized. The Kingdom demands nothing less than radical change. The Kingdom is a revolutionary magnitude that cannot be measured by our measuring sticks, and being immeasurable, it reveals the vanity of all we do. This is the source of the revolutionary vigor of our faith.

But also, the Kingdom is already present in the world—the seed in the ground, the leaven in the dough, the treasure in the field, the mustard seed, the faith of children, working in the world and changing it mysteriously. For the signs of that working we Christians are on the lookout, seeing the signs no matter how fragile, and being ourselves the signs of hidden life. So you can be open, you can be patient, you can be humble, you can even be submissive in your joy, you can be confident that God is working in the world right now, in fragile ways, and doing it through you.

When you keep these two visions together you get a double witness, and so we Christians do our actions in the world with reference both to the future, which we cannot achieve but only receive, as it is given us by God, and to the hidden present, where God keeps revealing God’s self in your own human acts of love and mercy and welcome, so that even the hill of The Skull may be a Paradise.

But it’s not a rose garden without the blood shed. And I don’t mean the blood of your enemy but your own. Thus the gory words of Colossians: “making peace by the blood of his cross.” Why blood? Why this gruesome reference to barbaric sacrifice to please the gods?

Here’s the point. Making peace is not the same as making nice. Making peace is not the same as all of us getting along. Not if peace includes justice. Your Christian actions of making peace are going to be hard work, risky, and costly, putting you in danger, you will have enemies, and it may cost you your life. You will be tempted like Jesus to save yourself. Your actions may not look like unity. Reconciliation is not the forgetting of our differences the repentance of our sins and the costly work of forgiveness.

If you want to work for peace and justice, keep the double vision in front of you, the vision of the kingdom of God at the end, already established up ahead, pressing down and judging everything, and the kingdom of God already today, in tiny shoots of tenderness growing through the cracks in the concrete. You do your little actions, and you pray them into the greatness of the future. You do your work and you let God gather your work into the larger whole. God is gathering in all things.

This is Ingathering Sunday, the final Sunday of the church year, when we have this vision of what God has been doing in the world since Jesus died and until he comes again. I invite you to believe that you are in the midst of it, and to rededicate yourself to action and to prayer. You are in the midst of it. When Jesus says, “Amen, Today,” it’s not just a man talking, it is God talking from the cross, for, as Colossians says, “in him all the fullness of God is pleased to dwell, and through him God is pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether in heaven and on earth, by making peace through the blood of his cross.”

Copyright © 2016 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Monday, November 14, 2016

Sunday, November 13: Not A Sermon

(We had a guest preacher on Sunday, Rev. Amy Nyland, but before her sermon I gave a pastoral word, and then we read out sections of the Belhar Confession. My people have asked me to post it all:)

Dearly beloved, this is not a sermon, this is a pastoral word. As you know, during our prayers of intercession we often pray for the President and others in authority. We will continue to do so on the first Sunday after the inauguration of Donald Trump. We will pray for him with charity and integrity. The church does not take sides on candidates nor on political parties. Those of us who voted Republican have the right to the outcome, and those of us who voted otherwise must not wallow in anger or resentment.

And yet something special must recognized. The fear and grief that came over so many of us last Tuesday night is real and justified, and not from being sore losers. The reasons are complex, and beyond my expertise, but the spiritual issue is the violence that was cultivated by the winner and exploited by his supporters. Violence — violence against immigrants, violence against black people, violence against brown people, violence against LGBTs, violations of women, violations of truthfulness, violence against the planet — we still have reason to fear it.

This violence is not new, it is apple-pie American. Violence is deep in our culture and our history no matter who is in power. But its current cultivation and celebration is what alarms us, and it tells us that this is a spiritual and ethical danger we Christians must bear witness to.

Two things, then: My next sermon series will be on violence, and how the Bible can help us. Second, the mission of the church is even more critical now: to be a community of the Lord Jesus Christ, that offers a great, safe space of absolute welcome, the practice of worship and service, and the vision of the Kingdom of Heaven. As today’s Gospel instructs us, “Do not be terrified. By your endurance you will gain your souls.”

We

Believe that God, in a world

full of injustice and enmity, is in a special way the God of the

destitute, the poor and the wronged;

We

Believe that God supports the downtrodden,

protects the stranger, helps orphans and widows and blocks the path of the

ungodly;

We

Believe that we must therefore stand by people

in any form of suffering and need, which implies, among other things, that

the church must witness against and strive against any form of injustice,

so that justice may roll down like waters, and righteousness like an

ever-flowing stream;

We

Believe that we must stand against injustice

and with the wronged;

We

Believe that in following Christ the church

must witness against all the powerful and privileged who selfishly seek

their own interests and thus control and harm others.

Therefore,

we reject any ideology

which would legitimate forms of injustice and any doctrine which is unwilling to

resist such an ideology in the name of the gospel.

From The Belhar

Confession

1986

Saturday, November 05, 2016

November 6, Proper 27, Haggai: Shaking Out Your Silver and Gold

Haggai 1:15b–2:9, Psalm 98, 2 Thessalonians 2:1-5, 13-17, Luke 20:27-38

This is the backstory to the prophet Haggai: The Babylonian Empire under Nebudchadnezzar destroyed the Kingdom of Judah and carted the people off to Babylon, with all the gold and silver from Solomon’s Temple, and they burned the Temple and leveled Jerusalem. The Jews began 70 years in exile.

Eventually Babylonia was conquered by the Persians, and the Persians allowed a group of Jewish colonists to return, and rebuild Jerusalem, and the Temple too. But the colony was poor, and the Second Temple was only a poor memory of the first one, and it stood unfinished.

The prophet Haggai comes along and he calls the people to finish the work, and he promises that God will shake the treasure out of the nations to restore the splendor of the temple, for, as he says, “The silver is mine and the gold is mine, and the latter splendor of this house shall be greater than the former, and in this place I will give prosperity, says the Lord of hosts.”

So then, Old First, I want you all to come back next week with every piece of gold or silver that you have, jewelry, tableware, whatever, and hand it over for the renovation of the sanctuary, to make it more splendid than before. And I want you to shake it out of your neighbors too. Just tell them that God says, “The silver is mine and the gold is mine!” Do this and I promise you prosperity!

I wish I could promise you prosperity as a by-product of your tithing to the church. I mean if what tithing means is that since all of your substance belongs to God to begin with, and thus you give back to God the first tenth of it—just that forces you to manage your money and be thrifty, which will tend toward your prosperity.

Well, as I said last week, there’s always at least some slight self-interest in every good thing that you do. No gift to God is pure, it can’t be helped, no tithe is pure, whether two percent or five percent or ten, there is in it some self-interest, and the financial interest of the church that teaches it. And yet the whole ideal of tithing is that you let the money go, you give it to God in order to surrender your control of it, and you want no recognition for doing it.

This problem of self-interest is also in our gospel for today. The Sadducees were the political party that was in power in Jerusalem. Their opponents were the Pharisees. The Pharisees taught the doctrine of the resurrection of all good Israelites in the coming Messianic age. But the Sadducees disagreed, because there’s no mention of resurrection in the Torah nor any eternal life. To believe such doctrines is to be contaminated by other religions. This is the only life we have, we are to serve God in the here and now, and whatever we have now is what God promised us. This is the best we’re going to get, so will you people please behave.

To teach this was in their interest, as they were the ones in power, and believing it, they kept the power, and controlled the money, and had nice lives. Their incentive for possession and control comes through in the test case that they offer Jesus: If, as required by the Torah, the woman marries seven times, and each one dies, then in the resurrection whose wife will she be?

Of course, it never occurs to them to ask the woman to make the choice. Even as late as 1968, the Reformed Church marriage liturgy included the question, “Who gives this woman to be married to this man?” The bride went from the custody of her father to the custody of her husband. Custody means control and it goes with property. So the test question of the Sadducees reveals an underlying interest in property and control.

It is typical of religion, even of the best churches, that our doctrines and disciplines are always contaminated by the interests of property and control. It can’t be helped, but it must be confessed. Just as we can never piously insulate our teaching of tithing from the financial interest of the church. We confess it, and we count on your maturity to value the message despite the messenger.

Jesus does not condemn the Sadducees. He even plays their game to argue from the Torah. Yet he moves the conversation to a higher level, from the What of the future to the Who of the future. The Why of the resurrection is not What you’re going to get from the resurrection, but for Whom you will be resurrected. You will not be resurrected for yourself, nor for your husband, nor for your wife, nor for your tribe nor for your nation. You will be resurrected for your God. You will belong to God and God alone, you will be free of every other social and obligation and sexual interest so that you may be free for God. (This, I think, is where God is drawing human social evolution.)

We are meant to be single, apparently, in the resurrection, single but not alone, single but not lonely, single but not incomplete, as the Lord Jesus himself was single and complete. Of course this raises questions. If we shall be resurrected bodily, and thus still gendered and with our sexualities, but forever single, will our genders and sexualities be eternally irrelevant? We are not told. No wonder it’s been easier to suppose that eternal life is only for the soul, and not for the body. But the Lord Jesus was resurrected in his body, and he proclaims it without explaining it.

So we accept the resurrection, not for ourselves, but for God. We accept the resurrection not in our own interest but in God’s interest. Not because eternity belongs to us but because we belong to God. Not as the reward we deserve but as the obedience we owe, not as the prize we earn but the praise that we render.

And if giving praise and thanks to God eternally sounds boring, as I think it must, and if you’d rather do something that has more interest, I guess we have to trust that what God has in mind for us will be more deeply satisfying than what we have known so far. And there will be music, that we know. And eating too, apparently. And wine. How it all works I do not know. But let me say it again, the message of Jesus is not the What of eternal life but the Whom of eternal life, the God for whom you will be resurrected.

What I dislike about the prophet Haggai is that he sounds like he’s wearing a white cap on which is written Make Judah Great Again. “You have no idea how rich you’ll be, and how splendid your temple will be, and we will make the other nations pay for it.” But at least he does say this: “My spirit abides among you, do not fear.” And that’s a real advance. God is fully present with God’s people already without the temple; before the temple is ready, God is fully among them anyway. Even in their circumstance, God is alive to them, and all of them are alive to God.

That’s what the Lord Jesus says: “Now God is the God of the living, not the dead, for all of them are alive to God.” When the Sadducees envision possessing and controlling, the Lord Jesus envisions living, really living, but living beyond possessing and controlling. Living alive to God, living open to God, and thereby open to others, and even more open to the world. It’s to enrich your life today, in this world, that you are promised the resurrection.

It means that your life today will not be wasted or rejected, nor the world, or the planet, and not even superseded, but revived, restored, renovated, and expanded and accelerated. So you can consider everything good thing and every good action that you do in the world today an investment in the life of the world to come, a seed you plant, for even though you yourself will pass away your life remains alive to God.

The vision of the Lord Jesus goes way beyond the Sadducees and the Pharisees because he sees the vastness of the love of God, the love of God beyond control and beyond the vindication of our rightful interests and beyond the boundaries of life and death. It’s all one. To enjoy eternal life is to give in and to surrender to this love that knows no bounds, this love whose name is God.

Copyright © 2016 by Daniel Meeter, all rights reserved.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)