Saul was born a Jew, but he was born a Roman citizen. He was not some Galilean country boy like Peter, James, and Jesus. Saul was born in what is now Turkey, in the city of Tarsus, the citizens of which enjoyed the special status of citizenship of the city of Rome, with all its rights and privileges attaining thereto. Saul had the right of access to Roman power, prestige, and pleasure, but he had committed himself to the opposite, to a rigorous form of Judaism. He had joined the strictest group of Pharisees—who will have been thrilled to have him, this guy who was fluent in Greek and even Latin, who had the freedom of the Empire, and could stand up to other Romans.

Saul was impassioned for the holiness of the Temple in Jerusalem in contrast to Capitol in Rome, for the purity of Jewish law against the laws of Rome, and for holding these tight until the Messiah would come and kick the Romans out and rule in Jerusalem once again. But these followers of Jesus were messing it up. They said the Messiah had come, and that he was ruling in heaven, not in Jerusalem. They infected the Temple with their heresies and prayers. They abused the Torah and did not keep kosher. They threatened the unity and purity of Israel and the sacred status of Jerusalem. Their movement had to be expunged for the survival of the whole.

Saul was that special sort of true believer whom we would call a fundamentalist. He saw himself as a very good guy who was so dedicated to the cause that he was not afraid to hurt people. It’s not that Saul did not love God. If Saul didn’t love God so much, he would not have persecuted him. You know the old saying: the opposite of love is not hatred, it is indifference. Hatred is not the opposite of love but the perversion of love, and it’s from perverted love that Saul is persecuting God. And why is his love perverted? Probably several reasons, including perhaps his motive of rejection, having been immersed in Rome, but what our lesson today suggests that it was his image of the God he loved.

Because he saw God a certain way, he thought he had to love that God a certain way, if even a way that was hurtful to others. Like Westboro Baptist, and let me recommend to you Jeff Chu’s book, because of his remarkable insight that what the Westboro people do is actually for love. We Christians have been doing this a long time in many ways, loving our image of God which causes hurt for other people. So have Muslims and Jews and Hindus and Buddhists. You can’t help but love God according to your image of God and how you see what God wants for the world. It’s a spiritual law that we become like what we worship. How you see God is how you see your neighbor and yourself. Saul saw himself as the dedicated one who would stop at nothing to defend the cause of the God he loved.

It’s similar with Simon Peter. Peter fancied himself as Jesus’ right hand man and bodyguard. He was the one who drew the sword to fight for Jesus at his arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane. He was one who did not run away, but followed from behind, and got himself into the courtyard of the high priest where Jesus was being tried, the only disciple there. And there, at the charcoal fire where the servants and soldiers were keeping warm, Peter, like some secret agent, denied that he knew him, and again a second time, but they did not believe him, and his cover was blown, and the third time he was vehement, only now to save his skin, and the cock crowed, and he was ashamed. He was the one who denied him because he was the only one who was there. If Peter hadn’t love Jesus so much he would not have denied him. Love can be so wrong. And Jesus has to convert his love. Which is what he does today at the charcoal fire on the beach.

It was the third week after Jesus’ resurrection, before his ascension, while Jesus is still bodily present on the earth, breathing its air and eating its food and accepting its gravity, but unbounded and unpredictable. Two times now they have seen the Lord. They believe he’s risen. But what does that mean? Now what? What’s next? We know the rest of the story, but those guys didn’t. So much for them is still uncertain. What did they imagine might be coming from the power of the resurrection?

Did they imagine that Jesus might be the new King David, trouncing the Roman Eagle and liberating the Promised Land, or a Jewish version of Alexander the Great, leading the armies of God across the world, as the companions of Mohammed would do six centuries later? I think Saul of Tarsus could have imagined that, and many Christians still want a modern version of this kind of thing—the expansion and prosperity and protection of Christian civilization in the world. That would be nice, but that is not the direction that Jesus shows them during these quiet weeks.

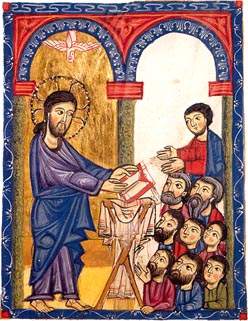

What you want depends on your vision of God. Do you picture God like Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, muscular, majestic, and powerful, or do you picture God paradoxically like a lamb, a lamb on the throne, a bit more powerful and lordly than a chicken on the throne, but not much. And if the lamb has been already killed, then God does not need our protection, thank you very much. The kingdom of God does not need our defending, and we do not need to strengthen it or build it, it wins by its weakness, thank you very much, so all you have to do is love. Love when they don’t want your love, love when it is inadvisable, and when people think such love impinges on God’s holiness, but God can take care of God’s own holiness, thank you very much.

To be a Christian is to convert your love, to convert your loves according your beliefs. For some of you this conversion is sudden and dramatic, like the turning of an enemy, like Saul. For some of you, like Peter, who have been with Jesus all along, your conversion is gradual, more intimate, and probably more painful, because it makes its way slowly through your guilt and shame and disappointment. Peter was a man of feelings, so he had to smell it, the charcoal smoke and the memory of his denial and and his shame and his fear and how his fear perverted his love. Paul is a man of intellect, and so he is blinded, to go inside himself and review himself in terms of this new piece of information he’s received. There are different ways God uses to convert our love. But all of them involve some suffering. Not the suffering of punishment, but the pain of our own selves and the feeling of our shame and the guilt. And you must come to love yourself, your shameful self, your guilty self, so that you can love other people too and suffer them.

What is your image of the power of the resurrection? What is your image of God? Early in the morning, a man walks out onto the beach, and he sees in the sand the packs and the tracks of his friends, and he looks out over the water and he sees them in their boats, and he sits down for a bit and watches. Then he gets up and gathers wood, thinking about each one of those guys in turn, how well he knows them and what their personal stories are, and then he builds a fire, and while it’s burning down to coals he goes down to the water, and he catches some fish (and we are not told how he does it) but then he comes back up the beach and he cleans them and guts them (don’t you love it, the Lord God cleaning fish), and he arranges them on the coals, and then he calls out to the disciples, and as he gets them finally fishing right, he kneels back down to turn the fish on the coals. He so loves the world. He so loves his friends, even that poor Simon Peter. "We’re going to have to have our talk." Saul of Tarsus will learn to love a God who acts like this. You can love a God like this.

Copyright © 2013, by Daniel James Meeter, all rights reserved.